Part 2: Foreclosure Fun & Games in US v. Google

Part 2 of 4 analyzing Judge Mehta's landmark US v. Google decision. Exclusive dealing cases are won and lost on foreclosure rates. What is it? Did DOJ prove it? And will the D.C. Circuit care?

Welcome back to Part 2 of our deep dive into the DOJ and States’ landmark victory in US v. Google.

There are many issues to unpack. And once again, I want to start once again by saying that while I will point out some areas where Judge Mehta’s 286 page opinion is vulnerable on appeal, it is an absolute of clarity when compared to the relevant market of large and complex antitrust cases. Today’s focus is going to be the “foreclosure” analysis in US v. Google, what it means, and if the court got it right.

But first, welcome to those of you who are joining us for the first time at Competition on the Merits! If you are enjoying this – please send to friends to subscribe, add yourself to the growing list of paid subscribers, or shoot me a note to let me know what you want to hear about. Or all of the above!

We began Tuesday with what I think is the portion of the opinion most vulnerable to reversal upon appeal: causation. If you are looking for a primer on Section 2 law or an analysis of why Judge Mehta applied the weaker causation standard when he should have applied the default “but-for” causation standard – you should start at Part I of our series: Causation Confusion: Why Judge Mehta Got the Causation Standard Wrong and Whether it Matters.

We started with Section 2 doctrine and the legal standard because the very first things an appellate court will look for are mistakes of law. Today – we shift toward more economics. Specifically, the question of what sort of economic proof that DOJ and the States set forth to prove its allegation that Google’s default contracts allowed it to maintain its monopoly and harm competition. I think it is useful to begin with the language in the Complaint itself about those contracts and why they are unlawful.

I want you to note two things about that language for now — and we will return to them: (1) that the agreements “denied rivals to the scale that would allow rivals” that would allow them to compete with Google; and (2) the description of the coverage of Google’s default contracts, i.e. “almost 60 percent of U.S. search queries.” Both are important. Not all exclusive dealing contracts – including those of a monopolist – violate the antitrust laws. Most are perfectly lawful. The idea is that Section 2 condemns the anticompetitive ones. But we have to identify them first. You will hear a lot of talk about foreclosure in commentary about the case. And today in this article. But we’re going to set up a bit of what that means and how economists (and courts) measure it so that we can (hopefully) distinguish the good exclusive dealing agreements from the unlawful ones.

To preview: two key questions courts are going to ask about when trying to identify the anticompetitive ones are going to be: (1) how much of the market do the exclusives “foreclose,” i.e. prevent a rival’s ability to compete; and (2) does that foreclosure have an impact not just on the foreclosed rival, but on the marketplace.

THE ANATOMY – AND LAW & ECONOMICS – OF AN EXCLUSIVE DEALING CASE

An Section 2 case alleging exclusive dealing contracts enable a firm to unlawfully acquire or maintain monopoly power has 4 key parts. Do not think of these as the legal elements to the claim. We are just dividing up key issues in a convenient way to do some analysis. Here are the key 4 elements:

Does the defendant has monopoly power?;

Is the defendant’s conduct is “exclusionary” rather than “competition on the merits”?

Does the allegedly exclusionary conduct have an anticompetitive effect? That is, does it harm the competitive process and consumers? And;

Do the agreements also have procompetitive effects?

We are mostly going to focus on elements 2 and 3 today. They are often blended together for good reason. And recall that last time we talked about the general Microsoft standard for Section 2 claims and how it spelled out the plaintiff’s prima facie burden. Here is the portion of that Microsoft framework language that applies to the plaintiff’s burden to establish the underlying exclusive dealing contracts are exclusionary and anticompetitive:

Whether any particular act of a monopolist is exclusionary, rather than merely a form of vigorous competition, can be difficult to discern: the means of illicit exclusion, like the means of legitimate competition, are myriad. The challenge for an antitrust court lies in stating a general rule for distinguishing between exclusionary acts, which reduce social welfare, and competitive acts, which increase it.

From a century of case law on monopolization under § 2, however, several principles do emerge. First, to be condemned as exclusionary, a monopolist's act must have an “anticompetitive effect.” That is, it must harm the competitive process and thereby harm consumers. In contrast, harm to one or more competitors will not suffice.

Judge Mehta adopts the Microsoft framework – so this is a good place to start. How a plaintiff shows an anticompetitive effect in an antitrust case depends on the type of conduct involved. You would want different proof for a merger between Coke and Pepsi than you would for a case where Pepsi alleges Coke maintains a monopoly in soda by buying up all of the shelf space. The Google case is very much like the matter – the core allegation is that Google’s default agreements make it so that rival search engines cannot get on the shelf. They cannot get access to enough consumer eyeballs to generate searches and compete with Google. There is a bit more nuance to it than that in some places – but the core theory of harm goes something (well, exactly) like this:

Google enters into default search contracts with Apple and Android OEMs;

Those contracts prevent rivals from being able to compete for distribution sufficient to achieve minimum efficient scale;

Rivals like Bing have their costs raised because they lose scale;

Because rivals like Bing operate at a higher cost, they are less effective rivals to Google and Google is able to maintain its monopoly for longer;

The longer monopoly means more harm to competition and consumers.

It is important you understand how this theory of harm works in order to really get what foreclosure is and is not. Let’s start with a picture.

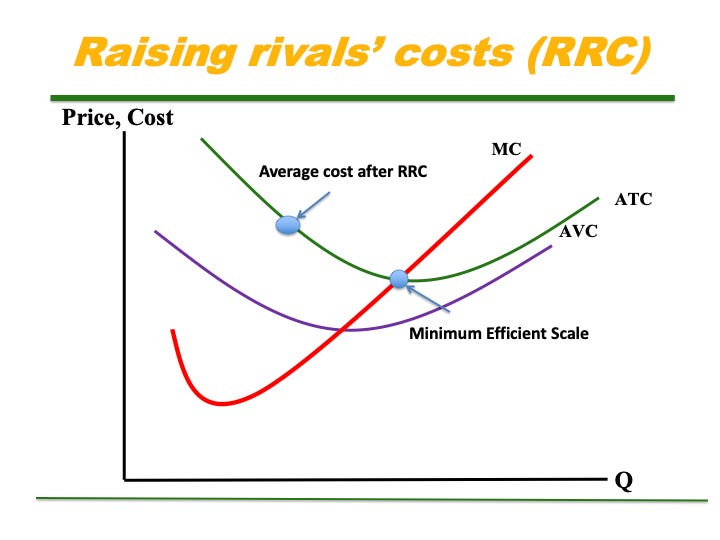

Think about the picture as a graph of Bing’s costs. You don’t need a lot of economics to understand this. But the idea of DOJ’s theory is that Bing is operating at minimum efficient scale – the very bottom of that curve labeled (ATC = Average Total Cost). A profit-maximizing firm like Microsoft wants to operate here. But then Google comes along and enters into exclusives that make it harder for it to get distribution and it moves to the point on the left – it moves up and to the left on the green curve to a point where Bing’s average cost is higher up that U-shaped cost curve. We won’t do a full on economics lesson on foreclosure here – but the idea is that Google engages in behavior that “raises rival’s costs.”

So what you say? Doesn’t a bunch of stuff that Google can do reduce Bing’s scale but is part of competition? It could steal Bing searches by simply being better!! Yes! Exactly the problem we need to solve. Lots of things result in harm to the rival, including procompetitive things. Competition itself “forecloses” rivals. But we want competition. Antitrust needs a way to immunize the good stuff that raises rival’s costs while condemning the bad stuff.

So what antitrust law does is breaks the plaintiff’s burden of proof into a few steps: (1) first show me (the court) that the rival itself was harmed by the practice – usually by showing “foreclosure” of some sort; and (2) show me this is the kind of foreclosure that actually harms competition rather than helps it. We call the first step “foreclosure analysis,” and for reasons I hope are clear it is necessary but NOT sufficient to establish anticompetitive harm. That’s kind of a big deal.

The second element is “competitive effects” analysis. We require the plaintiff to bear the burden of showing that competition and consumers were harmed not just Bing (or Pepsi). How can they do that? Two different ways. Plaintiffs can opt for “direct proof” of competitive harm. This usually means showing that the conduct resulted in higher prices, or lower output, or lower quality resulting from the conduct. This makes sense. We care about monopoly power because the monopolist does bad things to consumers. One option plaintiffs have is to show courts directly that the conduct had those effects on consumers.

The second method is “indirect proof.” Direct proof is often hard to come by in antitrust cases. Sometimes plaintiffs do not have it. All is not lost. Plaintiffs can show indirectly that the conduct – even though they cannot prove it – was likely to harm competition under some conditions. In exclusive dealing cases, plaintiffs do this by convincing the court that the defendant’s contracts really did move rivals from minimum efficient scale to some costlier (higher and to the left) point on the cost curve. They do this by convincing the court that the contracts “foreclosed” enough of the market that the rival cannot compete its way back to MES. It wants to compete its way back! It makes money if it does! But it cannot because the allegedly unlawful contracts prevent its ability to compete for that distribution because they are locked up into exclusives.

To foreshadow a bit, you should think about US v. Google as an “indirect proof” case relying almost exclusively upon evidence that the foreclosure rate is high and that the foreclosure results not just in harm to Bing and rival search engines but also that it harms competition. Here is Judge Mehta describing the alleged effects:

That is why the “foreclosure rate” becomes important in exclusive dealing cases. You will see all kinds of numbers associated with foreclosure rates, but it is important to keep that graph in mind. What the plaintiff wants is to show that the contracts prevented it from competing for so much distribution that it cannot possibly reach minimum efficient scale.

If Coke forecloses Pepsi from 10% of shelf space but it only requires Pepsi to have 40% of the shelf space to reach minimum efficient scale, an anticompetitive effect is very unlikely. If supermarkets can compete for those contracts every 30 days, it is very unlikely Coke can foreclose Pepsi from competing for access to those contracts. But if Coke can sign 10 year exclusives for 90 percent of the shelf space we have a much different, and better, story for the plaintiff.

In sum, plaintiffs can make out their prima facie burden directly or indirectly. In the absence of direct proof, they rely on foreclosure rates. What the court wants to see out of foreclosure rates – given that it is mostly about what happened to the rival and not to competition or consumers – is convincing evidence that the foreclosure rate is high enough that it prevented rivals from reaching minimum efficient scale. If you get that idea and repeat in your head three times that showing foreclosure is necessary but not sufficient for a violation, and understand why (lots of things that foreclose are good for competition!), you are off to a good start.

FUN AND GAMES WITH FORECLOSURE RATES

Once we understand the importance of foreclosure in “indirect proof” exclusive dealing cases, we can add one more analytical component before being able to fully dissect Judge Mehta’s foreclosure analysis. I want to talk a bit about fun and games both sides play with foreclosure numbers. Keep in mind WHY we are doing foreclosure analysis in the first place: we do not have direct proof of harm and would like to distinguish competition on the merits from conduct with an anticompetitive effect. Because we do not have evidence of the conduct directly making consumers worse off, it turns to whether distribution is so foreclosed that: (1) the rival cannot compete to achieve minimum efficient scale; (2) that foreclosure results in market wide effects that are present whether or not we can prove them.

As a legal matter, we know that courts in exclusive dealing cases REQUIRE a showing of substantial foreclosure – but nobody has any idea what exactly that means. As a legal concept, foreclosure is incoherent at best. In part this is because the landmark Supreme Court cases on the issue—cases like Tampa Electric and Standard Stations—predate the economic revolution in antitrust. The modern doctrine traces its origins to Standard Stations, where the Court made “foreclosure[] in a substantial share” of the market the test, without really elaborating further in any meaningful capacity.

These two cases have been read to stand for what I have described as the “naïve foreclosure approach”—one that looks to the share of outlets foreclosed as the primary determinant of anticompetitive effect, as an outcome-based approach—with the ends either condemning or justifying the means. This measure of foreclosure is fundamentally “naïve” because it is disconnected entirely from the modern theory of competitive harm in exclusion cases: Conduct that deprives rivals of the opportunity to compete for distribution, sufficient to achieve minimum efficient scale. I have an article with Alexander Kraszewksi on precisely this topic.

The naïve measure spits out the same result whether the dominant firm would enjoy the same share of distribution with or without the contracts at issue. It does not even attempt to measure the impact of any allegedly unlawful contracts, implicitly assuming that the dominant firm would get zero distribution in their absence. It simply presumes that high foreclosure shares are correlated with the ability to exclude rivals.

Left entirely open by the pre-economic revolution Supreme Court are questions about what sort of access is “proper”? As a matter of economics, foreclosure is often simply described as the amount of an input covered by a dominant firm’s contract, and often ignores whether the resulting contract was the outcome of an open and competitive process.

Naive foreclosure looks something like this:

NAIVE FORECLOSURE RATE = 100*DISTRIBUTION UNDER CONTRACT/

ALL UNITS OF DISTRIBUTION

Why is it naive? Naïve foreclosure is an “outcome-based” measure. The foreclosure share is calculated by the fraction of outlets foreclosed—To paint the picture, this is the practical equivalent of walking down the supermarket soda aisle, looking at how much Coke and how much Pepsi are on the shelves. But what naïve foreclosure cannot account for are the details that would explain the status quo—it ignores important pieces of the puzzle like the “competition for the contract” element of distribution—the fact that Coke and Pepsi compete to get on the shelf in the first place, by offering discounts, services, and payments to retailers. Fundamental to modern antitrust—and Section 2 in particular— is the notion that the antitrust laws protect the competitive process and not outcomes. The naïve approach to foreclosure assesses competition exclusively by the Coke-to-Pepsi ratio, without regard to whether, or how intensely, they competed to get there. To refine it a bit further, assume Coke and Pepsi are the only competitors for supermarket soda shelf space. They compete each month to enter into 30-day contracts with supermarkets. Suppose that Coke wins every time, because it offers superior terms, like lower prices or better promotional support. In equilibrium, Coke gets 75 percent of the shelf space and Pepsi the remaining 25 percent. Very few would describe Pepsi as foreclosed from access to competition in a meaningful way. Yet, the naïve foreclosure measure would conclude the foreclosure share is 75 percent—with likely liability and treble damages soon to follow.

Again, what is wrong with Naive Foreclosure? It tells us nothing about the competitive effects question. It spits out a number. But it leaves out two things: (1) what would happen without the agreements, i.e. do the agreements themselves impact competition?; and (2) are all of the units under contract actually foreclosed from competition? Or did Coke and Pepsi compete but one firm won? It would be misleading in the latter case to call those units of distribution foreclosed from competition because Coke beat Pepsi in the competition.

Plaintiffs play games with foreclosure rates. They generally prefer naive foreclosure. But the general game is to divide distribution into favored and disfavored distribution channels, e.g. perhaps they can argue that minimum efficient scale is really driven by eye level shelf space not all of the shelf space. This is a denominator game, i.e. shrinking the denominator to raise the share. Antitrust lawyers are very familiar with these games in the market definition context where plaintiffs want high shares and defendants want low shares.

Defendants play games with foreclosure rates. Defendants want bigger denominators (all distribution matters) and smaller numerators. Two numerator arguments go to the core of the anticompetitive theory of exclusion cases and are commonly invoked. One is that the units of shelf space are not actually “foreclosed” but rather the result of competition. When one sees Coke on the shelf or a search on Google one cannot immediately assume the unit was foreclosed from Pepsi or Bing. Perhaps there was a competition for the default. Perhaps consumer preference caused the selection rather than the default. Perhaps Coke would have had the shelf space with or without the agreements because retailers prefer it.

In each of these cases the defendant strategy begs the question: “What is foreclosure?” If we link the concept to the modern antitrust laws and the competitive process, mustn’t it mean something more than which unit is covered by the contract?

The defendant games usually ask for something other than “naive foreclosure,” I often describe it as “process-based foreclosure.” Courts are asked to do more than just count with their fingers what contracts cover which sales or searches. They are asked to link the foreclosure rate to the theory of harm. What makes a search foreclosed? Is it foreclosed if it would have gone to Google without the default? Ironically enough, the economic origins of foreclosure (a Krattenmaker & Salop paper from the 1980s) contemplate a process-based measure that would compare the percentage of the input foreclosed with the allegedly unlawful agreements to what would happen without them.

Don’t get me wrong. Courts often apply the naive measure. And sometimes that is good enough. For example, when we have little reason to believe that the defendant would get any shelf space or any searches without the contracts. There, it might make sense to attribute any sales to the agreement. The naïve approach remains quite common in courts to this day; many continue to apply naïve foreclosure analysis when confronted with tying and exclusive dealing cases alleging foreclosure from distribution sufficient to deprive rivals the opportunity to compete for minimum efficient scale. One notable example is the D.C. Circuit’s opinion in United States v. Microsoft. In the section of the opinion looking at exclusive deals with independent software vendors (ISVs), the court leaned heavily on Microsoft’s foreclosure of the two primary channels to find a prima facie showing of anticompetitive effect. This, by the way, is the DOJ’s strongest argument that the Court’s foreclosure analysis is not error. More on that later. Another example is the Third Circuit’s opinion in Dentsply.

There are many alternatives to naive foreclosure. Each process foreclosure method tries to link the foreclosure concept to the actual impact of the allegedly unlawful contracts in some way. Each explicitly embraces a counterfactual approach to measuring foreclosure; Krattenmaker and Salop’s seminal article proposed one, by framing the relevant antitrust question in terms of a “net foreclosure rate.” The authors defined net foreclosure rate as “the percentage of the suppliers’ capacity that was available to rivals before the exclusionary rights agreement was adopted but that is no longer available as a result of the agreement.”

I proposed another specific innovation for calculating foreclosure in a manner that better captures competition for distribution: but-for foreclosure (“BFF”). Google apparently relied upon this measure. The “BFF rate is defined as the difference between the percentage share of distribution foreclosed by the allegedly exclusionary agreements or conduct and the share of distribution in the absence of such an agreement.” These are just examples; there are other ways incorporate process-based approaches to foreclosure more closely aligned with modern exclusion theory. One can think of the shorthand courts use to supplement reliance upon foreclosure rates—like short-term contracts and switching costs—as a crude form of process-based foreclosure analysis. The value lies not in any one method but in going “under the hood” of the foreclosure rate to understand whether the competitive process itself is open and relating the actual impact of the allegedly unlawful contracts to market conditions.

You can find many courts embracing “process” based approaches to foreclosure as well. This article shares some examples. But to be clear, relying upon naive foreclosure is not sufficient to establish legal error. A better argument is that Judge Mehta’s specific reliance upon naive foreclosure so ignores record evidence that the agreements did not harm competition that foreclosure rates are insufficient as a matter of law to make out the requisite showing of anticompetitive effect.

In sum, but-for-foreclosure and other process based measures of foreclosure rely upon counterfactual analysis: what would happen with and without the allegedly unlawful agreements. They are about isolating the impact of the contracts at issue to understand whether they are procompetiitve or anticompetitive – the question at the very heart of the plaintiff’s prima facie case. They play a much larger role in cases, like this one, where plaintiffs rely on indirect evidence of competitive harm. Lots of measurement strategies are possible with foreclosure rates, but best practices are to relate them to the plaintiff’s underlying theory of harm and whether or not foreclosure was enough to stop the rival from achieving minimum efficient scale.

I think it is time to take our foreclosure lessons and apply them to Judge Mehta’s analysis.

JUDGE MEHTA’S FORECLOSURE ANALYSIS: IS NAIVE FORECLOSURE GOOD ENOUGH?

First, let’s talk about what Judge Mehta did when it comes to his foreclosure analysis. He certainly appears to agree that foreclosure cannot be any old number but must be sufficient to prevent the rival from reaching minimum efficient scale (i.e. “the critical level necessary”).

When it comes to calculating foreclosure – it is the good old fashioned “Naive Foreclosure Rate,” the fraction of searches covered by distribution agreements. Thus, Judge Mehta: “The court thus finds that as to the general search services market Plaintiffs have proven that Google’s exclusive distribution agreements foreclose 50% of the general search services market by query volume.

But if you have hung on this long you know that showing substantial foreclosure is necessary but not sufficient precisely because courts are concerned that high foreclosure rates could come about for any number of reasons not associated with harming competition.

Here is where things get interesting.

Google presses Judge Mehta to adopt two arguments we’ve already discussed: (1) but for foreclosure and (2) zero foreclosure because Bing could compete for defaults. I want to focus on the first. Google argues specifically that to get a better handle on the actual effects of the agreements and to disentangle the agreements from other, lawful reasons Apple or others might adopt Google as the default, a BFF measure is appropriate. For example, Google argued its own quality and Microsoft’s low quality led to many of those decisions or at least contributed to them.

Like most economists would, even DOJ’s expert Dr. Whinston agreed a counterfactual analysis would allow you to measure the impact of the default agreements more precisely:

I found Judge Mehta’s responses in light of all parties agreeing that a counterfactual analysis would shed brighter light upon the actual effects of the default agerements to be a bit of a red herring. And not very persuasive. Why not do a more accurate but for analysis? Judge Mehta’s response is something along the lines of: “because I don’t have to, so there?”

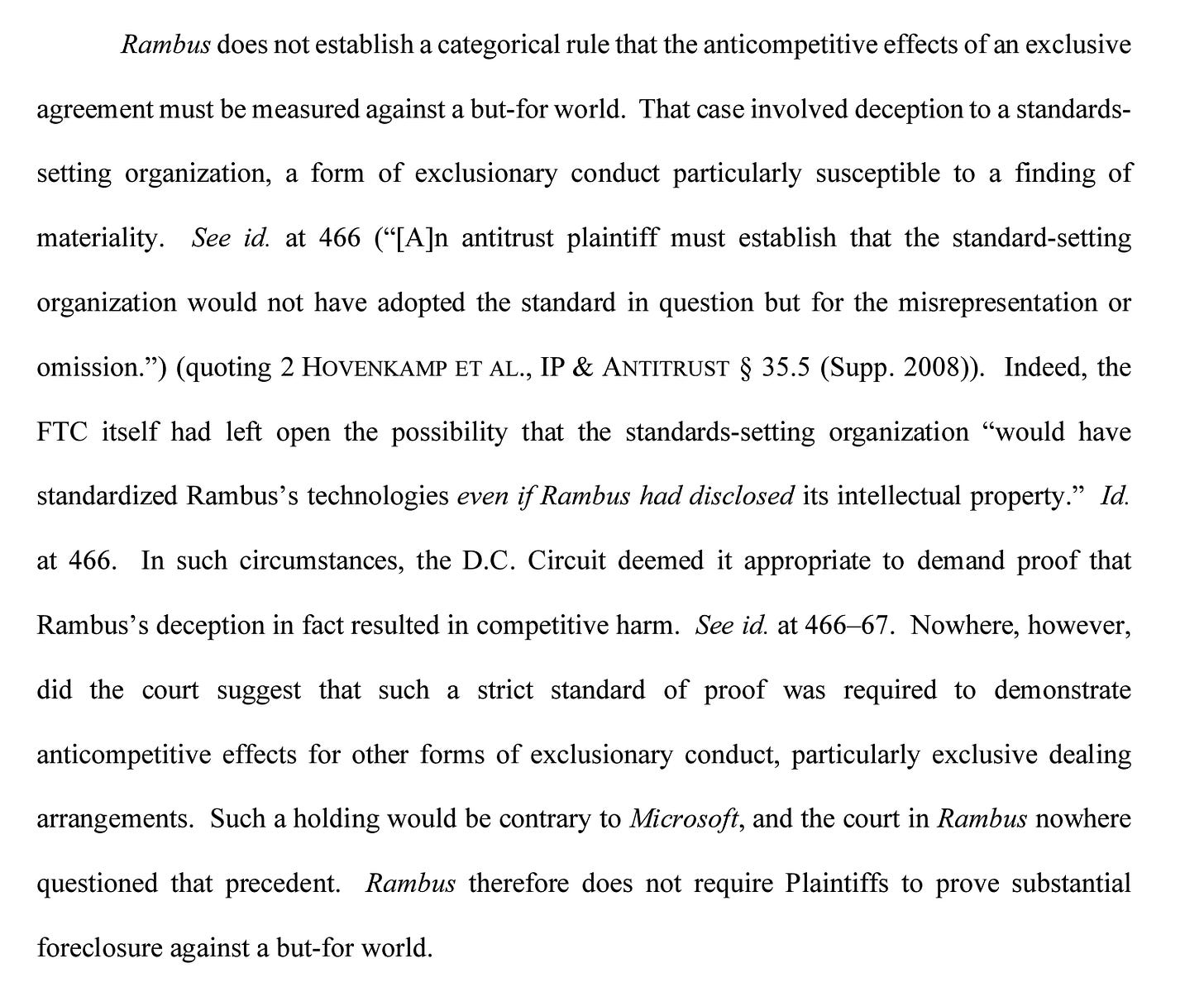

And even at that, Judge Mehta is right for the wrong reasons. Judge Mehta rejects the call for a but-for analysis when it comes to competitive effects analysis (via foreclosure) by appealing to case law about the causation standard. If you read Part I, you are already on top of this error. But here is the relevant excerpt from the opinion:

Nope. Nope. And more nope. Rambus establishes but-for causation as the default rule and Microsoft establishes the “reasonably capable of contributing” test as an exception for the exclusion of nascent competitors when anticompetitive effects are proven. Judge Mehta has conflated causation with competitive effects – a sort of classic antitrust analytical error, even among sophisticated players. But a mistake nonetheless. Antitrust analysts require counterfactual analysis to measure effects very frequently. It is indeed standard practice in many areas of antitrust law (e.g. damages, merger analysis, etc.).

So much for Judge Mehta’s first reason to reject but-for-foreclosure analysis. His second reason is that the court in Microsoft did not engage in but-for analysis. This is a better legal defense, though not much of an excuse on the economics. It is unclear whether the Microsoft record included a but-for analysis of foreclosure. The record in front of Judge Mehta clearly did. Foreclosure rates are not meaningful with respect to competitive effects on their own. They may be made meaningful when compared relative to minimum efficient scale. They may also be made meaningful when compared to a but-for world. It is curious why the court would throw out the information when available.

Judge Mehta finds comfort in other courts rejecting “zero foreclosure” arguments in contexts where the defendant has exclusives in the most efficient distribution channel but others are available. He takes these decisions literally, but not seriously.

For example, Judge Mehta compares Google’s arguments about zero foreclosure to a handful of other cases:

But neither Eisai nor Allied Orthopedic stand for the broad proposition that there is no market foreclosure when a dominant firm leaves some alternative ways for customers to access rivals. Microsoft rejected that very proposition. For instance, it treated as exclusive Microsoft’s agreement with AOL, even though it permitted AOL to distribute Netscape if customers requested it. 253 F.3d at 68. It did the same as to the OEM agreements, which left open internet downloads and mailings as a means for users to reach Netscape. Id. at 64, 70; see Microsoft, 87 F. Supp. 2d at 53. The court in Microsoft did not say that these contracts caused zero market foreclosure merely because Internet Explorer had other, less-efficient means of reaching users.

Of course, Google’s proposition was not that the existence of alternative methods of distribution require a finding of zero foreclosure. And Microsoft explicitly found that the foreclosure was substantial enough to prevent rivals from reaching minimum efficient scale. Here, Google invited a further look under the hood to understand whether the searches were foreclosed or not – and the court simply declined.

There are some really good reasons to think that a counterfactual analysis would shed more light on the precise effects of Google’s contracts. Reasons the court acknowledges. For example, one hypothesis is that Microsoft’s own low quality (and the gap with Google’s quality) would lead Apple and Android OEMs to choose Google regardless. It is very difficult – in fact, it defies logic – to attribute to foreclosure arising from Google’s agreements searches that would go to Google with or without those same contracts. Greg Werden makes this point nicely:

But if operating at a much smaller scale than Google makes rival search engines uncompetitive, their fate was sealed when Google achieved a dominant share. The government posits no scenario in which any rival search engine could have substantially closed the scale gap…. If the government’s scale contentions are fully credited, the conduct that is at the heart of the case did not maintain Google’s dominant share. And any conduct that could not have maintained dominance most likely served a legitimate purpose. One way or another, the elements of the monopolization offense cannot be established under the government’s view of the facts…. But the government does not contend that rival search engines ever posed a real threat to Google’s monopoly. Indeed, it claims to have proved just the opposite

Judge Mehta’s response is incomplete:

Google also maintains that the quantity of user data is less important than how it is used, and if its rivals had Google’s business foresight and drive to innovate, they too could win default distribution. But that position blinks reality. Apple’s flirtation with Microsoft best illustrates this point. Microsoft has invested $100 billion in search in the last two decades and its quality now matches Google’s on desktop search. Yet, Microsoft’s failure to anticipate the emergence of mobile search caused it to fall behind, and with Google guaranteed default placement on all mobile devices, Microsoft has never achieved the mobile distribution that it needs to improve on that platform.

First, it is incomplete, because as Geoff Manne has argued, it makes little sense to attribute to Google’s default contracts decisions that Microsoft made independently.

Second, in cases where distributors might prefer one product to another and so there are multiple reasons why distribution might be “foreclosed” from a rival, counterfactual analysis is especially valuable. Google argues the quality difference is exactly such an explanation. It also argues the defaults are not as important. Counterfactual analysis allows one to isolate the impact of the agreements.

Oddly, Judge Mehta’s opinion is replete with appeals to economic reality over theory. I count at least a dozen invitations to favor market realities over theory or assertion. And yet, when invited to get closer to market realities by engaging in counterfactual analysis to rule out spurious correlations, Judge Mehta declines again and again.

IS NAIVE FORECLOSURE ANALYSIS LEGAL ERROR?

Not really. Sort of. Sigh. OK, let’s talk.

As discussed, plenty of courts have engaged in naive foreclosure analysis. In the absence of direct evidence, they have gone on to infer anticompetitive effects from the combination of a high foreclosure share and other facts consistent with the rival not being able to compete for minimum efficient scale. So in short, no it is not legal error for Judge Mehta to rely upon naive foreclosure analysis even if it is not best practices. It is probably not legal error for Judge Mehta to rely upon naive foreclosure analysis even when it was offered up to him and the conditions of the case (factually) make it much less reliable than counterfactual analysis. While I would much prefer the law to require counterfactual analysis – I wrote a whole article on it and (in my mind) coined the modern usage of the term “but for foreclosure” – it is not the law today.

Score 1 for Judge Mehta. But not so fast my friends. Here are a few more serious arguments that may find success on appeal.

First, what is required – and I promised to come back to this — is a showing of anticompetitive effect. Google may well argue that without but-for analysis of foreclosure, the naive measure simply cannot be sufficient to satisfy the plaintiff’s prima facie case because it does not distinguish (by definition) competition on the merits from exclusion. I like this argument. I do not think it has been made in many cases. But it is perfect here. These arguments largely go to the conclusion that any naive foreclosure number can tell you about “significant foreclosure.” In modern antitrust, significance is about market-wide effects. And naive foreclosure simply cannot get you there.

Second, Judge Mehta’s OWN reason for not doing counterfactual analysis is wrong. He relies on causation law to say it is not required. I can imagine an effective argument that at a minimum, we get a reverse and remand to engage in a counterfactual foreclosure analysis. Recall that the Microsoft court may have done naive foreclosure analysis, but combined it with specific findings about minimum efficient scale that were not replicated here.

But that begs the question …

WHAT WOULD COUNTERFACTUAL ANALYSIS SHOW, ANYWAY?

I want to separate out two points that are really important. In Part I, we focused on causation. Our conclusion was that the Rambus “but-for” causation standard applied. I think you are going to see – or at least should see – is that counterfactual analysis is required one way or another.

I want you to be ready for these arguments because the differences between them can be subtle. The Rambus / causation version of this argument is that but-for analysis is required to establish causation. The competitive effects version of the argument is that but-for analysis is required because the plaintiff cannot meet its prima facie burden without it in these circumstances. Both are pretty good appellate arguments! If I were Google I would be lining up a bunch of scholars for amicus briefs making these points (among others).

But they are different points. And the causation point is required by law – and thus more powerful – and the effects point “might” be required by law but takes a few more moves to get there.

But let’s say Google wins on those points. The D.C. Circuit might dive into the but-for analysis in the record to reach its own conclusion. Or it might reverse and remand. But either way, an analysis of the but-for evidence is called for. You read me hopefully to get ahead of the game and not just catch up to it. So what then?

First, there is a beautiful natural experiment set up for counterfactual analysis. If you were Google what you want is a situation in the absence of the allegedly unlawful agreements to see what kind of search share you got then. The difference between what Google gets with the defaults compared to what it gets in the absence of them (say with a choice screen) tells you a bit more about the impact of the agreements themselves. DOJ’s own expert said this information would be higher quality about isolating the impact of the allegedly unlawful agreements from other explanations.

There is plenty of record testimony on this point. Here is Google’s expert Kevin Murphy at trial:

While Google’s Expert (Kevin Murphy) and DOJ’s expert (Michael Whinston) argue a bit over the size of the empirical estimate of foreclosure in the but-for world, i.e. comparing the real world to the world with a choice screen, they agree the effect is small.

This is a big deal. To go back to our Coke and Pepsi example, consider a case where Pepsi sues Coke and alleges that its shelf space agreements violate the antitrust laws. With those agreements, Pepsi presents evidence that Coke gets 80 percent of the shelf space in the relevant market. Coke responds by showing that in the absence of those agreements (maybe in markets where it does not have them or maybe from a different time period before it started to use them) Coke still gets 75 percent of the shelf space. In what world would it be appropriate for the court to conclude that the agreements foreclose 80 percent? Most of us – even without any economic training – would say the marginal impact is about 5%.

Here we seem to have a case where ALL parties agree the actual impact of Google’s allegedly unlawful agreements is small based upon accepted methodological approaches. Both parties. The best the DOJ and its expert can come up with is to contend that the best available methods of measurement are not always required by law. OK I guess. But I would not gamble my own money expecting the D.C. Circuit to be quite as accepting on appeal.

The existence of counterfactual evidence in the record feels like an important difference between Google and Microsoft. It was the type of evidence the Microsoft court probably wished it could have had but did not because it was the exclusion of nascent technology not even in the market yet. That has bearing on the causation standard as we have already explained. But I would think it will have an impact on the appeal. There is record evidence of counterfactual analysis sufficient to make a couple of pretty powerful arguments no appeal: (1) but-for analysis is required under Rambus when it comes to causation and a but-for analysis reveals no causation because Google’s quality meant they were going to get distributed anyway (just like in Rambus); and (2) the plaintiff could not have plausibly met its prima facie burden without a but-for-foreclosure analysis – and under that analysis the agreements do not result in substantial foreclosure.

Keep an eye on both of those arguments. Next week we will turn to the $64,000 question: “if the defaults are not so powerful why pay a gazillion dollars for them?” And we will talk a bit about remedies and what comes next.