The Robinson-Patman Act Meets Economics

In Part 2 of our 3 part series on the Robinson-Patman Act, we turn to the economics of the RPA. What impact will FTC RPA enforcement have on competition and prices? Plus, some myth-busting.

Welcome back to Competition on the Merits! Today I continue with Part 2 of a 3 part series on the implications of the FTC’s Robinson-Patman Act agenda. Part 1 examined the dysfunctional relationship between the RPA & consumer welfare. Part 2 turns to economics. Let’s start with a little bit of myth-busting.

The myth? The longstanding, bipartisan criticism and rejection of the Robinson-Patman Act on legal and economic grounds is some sort of Chicago School conspiracy rather than, well, the result of a basic understanding of antitrust law, a touch of price theory, and an objective evaluation of the empirical evidence.

Here are some recent examples of the myth that the Robinson-Patman Act is really just misunderstood. By everyone. Ever.

“There is no evidence that the Robinson-Patman Act causes higher consumer prices or discourages lower prices; those are just ipse dixit attacks by laissez faire lawyers, not economists.”

Mark Poe, Antitrust Magazine (April 05, 2024),

“To my knowledge, some 86 years after its passage, there is not one empirical analysis showing that Robinson-Patman actually raised consumer prices.”

Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya, Returning to Fairness (September 22, 2022)

My last post focused upon solving what I described as the Robinson-Patman Act / Consumer Welfare Conundrum. That is, why is it the RPA has more successfully resisted economic analysis than its sister antitrust laws. It is an important question and one that I think is important to understand in order to think about the FTC’s upcoming cases against various product suppliers and distributors alleging that larger discounts to larger retailers cause secondary-line harm to competition and thus violate the RPA. I concluded that while lower courts in RPA cases have resisted the focus on interbrand competition and consumers shared by the rest of the antitrust universe, there are some reasons for optimism that the upcoming wave of secondary-line RPA enforcement by the FTC ends with the courts correctly interpreting the RPA to take consumers into account and requiring harm to competition rather than competitors before a finding of liability.

I want to focus on something different here: economics. The quotes that start this column – from Mr. Poe and Commissioner Bedoya, respectively – are common fare for RPA advocates. The argument goes something like: we know RPA enforcement will help some specific competitors (smaller retailers) so in the absence of demonstrable harm to competition, is it not a good idea? Commissioner Bedoya says he is aware of zero economic evidence about the effects of RPA enforcement. Mr. Poe goes further to claim (without any empirical evidence of his own) that, “In real-world application, private enforcement of the Robinson-Patman Act encourages lower prices to be available to more customers, given that the disfavored plaintiff is invariably asking for the favored purchaser’s price.” Mr. Poe goes still further to argue that it is just “laissez faire lawyers, not economists” arguing that RPA enforcement raises prices through a series of “straw men and framing devices.”

I suppose I’m both a laissez faire lawyer AND a laissez faire economist, but I’ll try to only wear the latter hat for this entry so as to speak directly to Mr. Poe and Commissioner Bedoya on their own terms (if not a tad more respectfully, in the case of Mr. Poe): you are both wrong about the economic evidence.

In this post I will explain why the misconception about the economic evidence has persisted, but also provide some direct evidence that relates precisely to the conduct to be alleged unlawful in the FTC’s upcoming secondary-line RPA claims. Indeed, the evidence is precisely the type of evidence I would encourage RPA defendants to offer in their own defense through expert economic testimony. Specifically, RPA defendants should show that the larger discounts to favored purchasers result in an increase in competition (not injury or reduction as required by 2(a) of the RPA) as evidenced by increases in output and reductions in the price compared to the world without the allegedly unlawful discounts. For the lawyers objecting that there are many secondary-line 2(a) RPA cases that hold evidence of mere lost sales by the disfavored purchaser are sufficient to satisfy the plaintiff’s prima facie burden – I hear you. Please go read the last post. I do expect these arguments are less likely to prevail in district court – though they are completely consistent with the RPA’s requirement that “competition,” be injured – than they are to prevail in appellate courts. I am optimistic that one of these FTC cases reaches the Supreme Court and there is plenty of reason to believe after Reeder-Simco that SCOTUS will bring secondary-line RPA cases into the antitrust family (as they did with primary line cases in Brooke Group 31 years ago).

Back to it.

Let’s start with a brief explanation of why there is so much debate over what economists know and do not know about the welfare effects of price discrimination. Economists have written volumes upon volumes on price discrimination, its various forms, and its effects on welfare. Varian’s (1989) survey chapter remains a great place to start. Ben Klein on Price Discrimination and Market Power is also a good place to start. But the first thing to understand in this debate is that: Lawyers and economists mean something different when they talk about price discrimination.

Economists generally use the price discrimination label to describe any sort of pricing that results in different rates of return for purchasers. It could be tying or bundling razors and blades together, resulting in different package prices for different types of consumers. It might be movie theater discounts or two-part tariffs. As Varian puts it, “the issues of concern to economists are those of efficient pricing.”

Price discrimination is ubiquitous in competitive markets and takes myriad forms. So economists might write a very sophisticated empirical paper measuring the welfare effects of third-degree pricing schemes where the seller reduces the price of the razor and increases the price of the blades. For lower intensity shavers, we move down the demand curve and make more sales of razors than we would otherwise, but high-intensity shavers pay more for the package (because we’ve put the upcharge on the blades). Does welfare go up or down? Both. Unsurprisingly, when economists try to measure the global welfare effects of these practices – practices that often occur in highly competitive markets — sometimes they are positive, sometimes negative, and sometimes neutral. But notice the question here is just about whether the price discriminating monopolist has priced efficiently relative to the monopoly pricing benchmark. We are using data to sum up the welfare effects across the consumers that are made better off by the price discrimination, the ones who are made worse off, and making a statement about global welfare. We are not saying much about competition.

Similarly, the corner coffee shop might decide to give milk out for free to coffee drinkers rather than charge for it at the register. The price of coffee increases marginally to cover the cost of cream. Black coffee drinkers lose compared to the “charge for cream” world and are subsidizing the cream and coffee drinkers. Price discrimination? Absolutely, to economists. Possible that net welfare goes down because in some markets black coffee drinkers lose more than creamed coffee drinkers gain? Absolutely. Much to do with competition? Not so much. Just a statement about welfare losses compared to an efficient pricing benchmark.

Still, we do know something about welfare effects in these situations. An increase in output is generally (subject to some well known exceptions) a sufficient condition for an increase in welfare. As Varian summarizes:

[W]e can expect that allowing price discrimination will typically enhance welfare if it provides a means of serving markets that the monopolist would otherwise not serve. Conversely, if the size of the market does not increase under price discrimination, there can be no net increase in consumers' plus producers' surplus. Thus, it would seem that an economically sound discussion of whether price discrimination is in the social interest should focus on the output effects. However, as we have seen above, this consideration has not played much of a role in the legal discussion of price discrimination.

Lawyers mean something quite different. The RPA refers to literal, nominal price differences. Not rates of return and pricing structures that result in different rates of return for different types of consumers. Just price differences. When well meaning economists are asked to answer the question: “What does economics say about price discrimination?” They give the incomplete but understandable reply: “The welfare effects of price discrimination are ambiguous and so we do not have much to say here.”

Mr. Poe and Commissioner Bedoya and others are indeed onto something here in the claim that there is zero empirical evidence to support the view that RPA enforcement is bad for consumers. By the way, when did the standard for evidence supporting a course of regulatory action become “there is no study demonstrating that the action I intend to carry out is unequivocally harmful”? In any event, what they are onto is not what they think it is. Indeed, I am also not aware of any empirical study that has tried to net out welfare effects from RPA enforcement. It would be near impossible to do! Do we mean primary-line cases or secondary-line? Before or after Brooke Group? There have certainly been smaller scale attempts to evaluate the RPA empirically. But most of the time, critics have argued from economic first principles. Fair enough. Economic first principles speak more convincingly to some than to others.

The Mr. Poes and Commissioner Bedoyas of the world reject the basic economic analysis and see the lack of silver bullet evidence against RPA evidence as a license to proceed. This is a sort of “reverse” Nirvana Fallacy. Typically, the Nirvana Fallacy involves relying upon idealized, perfect counterfactuals to support a course of action: Let’s block this merger because the current market is imperfect and the remedy will certainly move us closer to the ideal outcome. Here, RPA defenders and apologists claim there is no evidence RPA enforcement is an absolute failure and thus it must be a good idea to do more of it.

But if first principles will not satisfy – let’s give the RPA defenders the evidence they want. What is that? Ideally we would like to pin down the conduct the FTC is alleging is unlawful and putting on trial in the court of consumer welfare. From the universe of studies of price discrimination, most are irrelevant to studying the conduct the FTC and RPA are focused upon: Suppliers offering relatively larger discounts (of soda, alcohol and various grocery products) to larger retailers such as Walmart and Target than they do to other retailers selling the same products.

Going back to the actual language of the RPA: what exactly do know about whether supplier discounts offered to larger retailers than their rivals “injure[s], destroy[s], or prevent[s] competition with any person who either [i] grants or [ii] knowingly receives the benefit of such discrimination”?

As I discussed last time, in secondary-line cases, its own words focus on the effect of the discounts on competition between the large retailers receiving the discounts and their rivals. The Supreme Court tells us that “interbrand competition” should guide the competitive analysis – even in RPA cases. Here, that is competition at the retail level. There are a few things that, in an ideal world, we would want to know to answer this question:

What happens to prices and output in those retail markets? If prices fall and output goes up, we know that interbrand competition has been intensified, not “injured, destroyed, or prevented.”

What do the “disfavored” retailers do in response to the discounts?

What happens to consumer welfare in those markets?

These are the critical economic questions behind secondary-line RPA enforcement. And it is simply false that there is no economic evidence reading on them.

To repeat, the behavior we are studying is the following: competing suppliers who distribute their products through multiple retailers and offer larger discounts to larger retailers. We can set aside the voluminous economic literature on price discrimination with metering ties, razors and blades, in bargaining markets, and so forth and so on. The FTC has already told us what these suits are going to look like. It is no secret this is about large retailers: Walmart, Amazon, Target, Costco, and maybe a handful of others.

So when we zoom in on that setting, what do economists know about what happens to competition when Walmart receives large discounts for the same product sold through rival retailers? That’s exactly the question the RPA cases should focus on. It is exactly the question Mr. Poe, Commissioner Bedoya, and others incorrectly claim economists are silent on. And it’s a great question to ask if you’re interested in whether the RPA makes any sense at all. On top of that, the answer has a lot to offer in terms of the type of economic evidence that can be used to defend individual RPA cases. Economics informing specific litigation, law, and policy at the same time? What’s not to like?

RPA Enforcement Seeks to Prohibit Walmart and Other Large Retailers From Receiving Large Discounts – What Effects Does That Have on Competition and Consumers?

So what do economists know about what happens to competition and consumer welfare when Walmart (to pick one firm) receives larger discounts relative to rivals? Plenty.

There is an economic literature that gets at exactly this question. In particular, economists have studied the competitive dynamics of Walmart – and its ability to extract discounts based upon its large size – entering the grocery retail market. Hausman & Leibtag (2007) employ a well known approach (developed by Hausman) to assess the welfare effects when Walmart enters a new retail market. Using scanner data from grocery retail sales in markets where Walmart enters (and where it does not), Hausman & Leibtag are able to measure directly two effects we are very interested in: (1) the direct price effect (i.e., when Walmart extracts large discounts from suppliers, how does that translate to prices and what sort of impact on competition and consumers does that have?); and (2) the “indirect” price effect (i.e., do competing retailers respond to Walmart by lowering their own prices to attract sales?). How large are those direct and indirect price effects? And how much does it benefit consumers? The answers to these questions can also help us relate back to the RPA’s question: Do differential discounts to Walmart injure, destroy, or prevent competition at the retail level? Or do they enhance it?

Evaluating over 20 different food products across 34 geographic markets, the authors find that entry by a large retailer such as Walmart results in substantial gains for consumers PRECISELY because Walmart is able to extract large discounts and thus sell at lower prices. On average, Walmart prices are 27% less than competing supermarkets for the same products.

Using econometric analysis to isolate the direct effect of Walmart’s grocery pricing on competition, the authors find an average decrease across all food categories of 3.0%.

The authors translate these figures to consumer welfare from the entry and expansion of Walmart and other non-traditional retail outlets. Specifically, the competitive advantage of Walmart and larger retailers in these markets is precisely that they are able to extract larger discounts from suppliers and translate them to lower prices. Here, the consumer welfare contributions from Walmart to consumers in food retail is staggering. Hausman & Leibtag find a benefit of approximately 20.2% of all food expenditure. This “direct” effect is the benefit to consumers from intense competition from Walmart for their business.

This is an enormous benefit to consumers who gain increased purchasing power for food as a result of Walmart’s (or other large retailers) entry and expansion to compete with grocery stores.

But that is not all. These are not just gains to an unnamed blob of consumers. This is not just about efficiency. These are real dollars going to real people. Hausman & Leibtag go a bit further in their analysis to identify who the beneficiaries are when the Walmarts of the world are able to extract larger discounts from suppliers and translate them into lower prices.

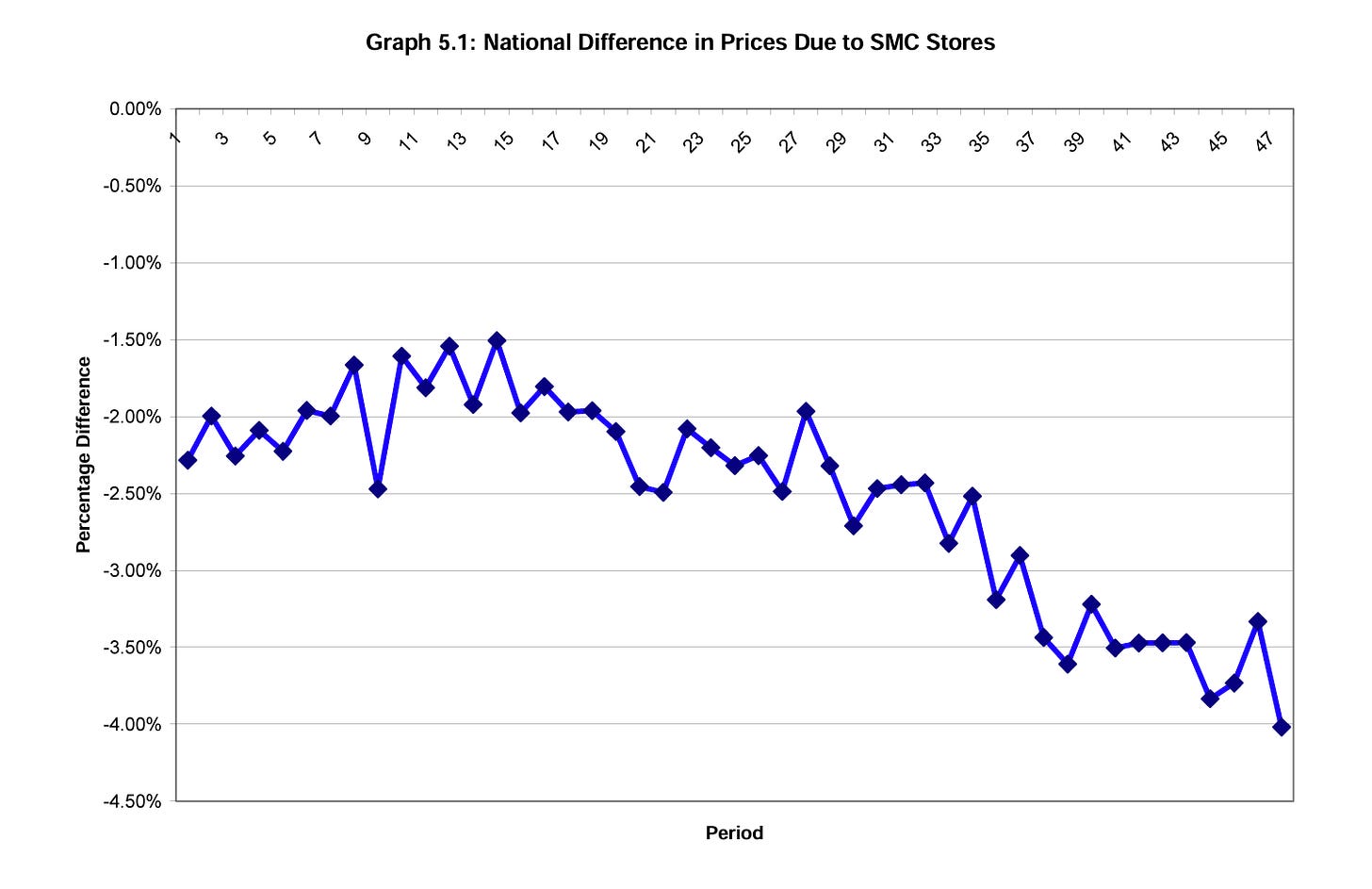

The chart below shows their findings and takes into account distributional effects. The compensating variation the authors measure is economists’ speak for “how much money would you have to pay the consumer to give up its choice to shop at Walmart or another superstore?” The answer: a lot. You’lll see below that the figure ranges between 20 and 30 percent of all grocery expenditures. But pay attention to the X-axis. The authors measure this compensation variation for different income level consumer groups. The biggest beneficiaries of Walmart’s pricing – that is, of those larger discounts alleged unlawful under the RPA – are the poorest consumers. Indeed, households making less than $10,000 benefit from compensation (from lower prices) in the range of 29 percent of household food expenditure. Basker and Noel (2009) find similar results.

There is another really interesting effect identified in the literature I want to focus upon for a few reasons. The effect is simple and quite predictable: when Walmart reduces prices, rival supermarkets and grocery retailers respond – that is, they compete – by reducing their own prices. Hausman and Leibtag separately identify the effect that arises when existing grocery stores lower prices in response to Walmart. That additional competitive response accounts for an additional 4.8% in consumer surplus. And this effect certainly arises from increased competition with the retailers. Indeed, the effect increases in magnitude the closer in proximity Walmart is to competing retailers.

There is more. It is not just low prices that benefit consumers, but also sufficient access to food in the first place. Courtemanche et al. (2018) evaluate the impact of Walmart Supercenter entry and expansion into new markets on food insecurity. The Walmart business model is based precisely upon the foundation of making supply chains more efficient, which is one of the reasons Walmart is able to extract large discounts from suppliers. So, what is the effect of Walmart entry – discounts and all – on food insecurity? Using data from the 2001-2012 waves of the December Current Population Study Food Security Supplement, Courtemanche et al. find that “the entry of Walmart Supercenters helps to alleviate food insecurity across most measures for both households and children. The effects are strongest for low-income households and children but are still sizeable for middle-income children.”

Commissioner Bedoya’s signature speech endorsing RPA enforcement relies on a classic “efficiency versus fairness” framing device. He writes: “As for me, my focus is on people living paycheck to paycheck. For me, that’s what antitrust is about: your groceries, your prescriptions, your paycheck. I want to make sure the Commission is helping the people who need it the most. And I want to make sure we don’t leave rural America behind.” Frame accepted, Commissioner.

Commissioner Bedoya’s FTC tool of choice – RPA enforcement – would do more significant harm to those folks living paycheck to paycheck he purports to focus on more than any single antitrust policy endeavor since the Sherman Act was passed into law. The obvious impact of RPA enforcement, if successful, will be to penalize and enjoin differential discounts and force uniform pricing. The effects are obvious. And they will do the most damage to the poorest consumers. It is reasonable to ask those calling for more “fairness” in antitrust enforcement: – What exactly is fair about raising the grocery bill of our lowest income citizens by 20-30 percent in the name of subsidizing certain supermarkets and grocers?

Shall we summarize the findings for the RPA lovers in the back of the room? And perhaps at the FTC?

The heart of the FTC’s RPA clams will be that Walmart and other large retailers such as Target, Costco, and Amazon are able to extract larger discounts from suppliers than rival supermarkets and grocery retailers

Hausman and Leibtag (and others) find that Walmart’s entry and expansion into grocery retail – in large part due precisely to its ability to secure those discounts – improve consumer welfare by over 20% as a result of Walmart passing on those discounts in the form of lower prices

Hausman & Leibtag also find other retailers respond to Walmart’s price reductions by competing with their own price reductions, which increases consumer welfare another 4.8% on average

The average impact on consumers across product categories and markets is therefore approximately 25% – that is a simply enormous increase in welfare

Hausman & Leibtag find these benefits are disproportionately large for the lowest income consumers

Courtemanche et al. find that competition from Walmart and other large retailers results not only in lower prices, but also significant reductions in food insecurity

Collectively, this evidence examines the effects on competition, welfare, and consumers of exactly the conduct the FTC seeks to declare unlawful in its coming RPA suits

Does This Type of Evidence Have a Place in Secondary-Line RPA Suits?

The answer is, in my view, an unequivocal “yes.” My earlier post spells out the argument at length. But let’s review the RPA’s language once again:

the effect of such discrimination may be substantially to lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce, or to injure, destroy, or prevent competition with any person who either [i] grants or [ii] knowingly receives the benefit of such discrimination, or [iii] with customers of either of them…

The RPA language conventionally relied upon in secondary-line cases – that is, RPA cases alleging differential discounts from suppliers to retailers harms competition among retailers by favoring one over others – is the last prong, requiring the effect of such discrimination be “to injure, destroy, or prevent competition with any person who either [i] grants or [ii] knowingly receives the benefit of such discrimination.”

Notice that the RPA requires injury, prevention, or destruction of “competition with any other person who grants or knowingly receives the benefit of such discrimination.” In other words, a prima facie RPA case requires evidence that interbrand competition at the retailer level between Walmart and other retailers selling the products at issue was harmed.

I am fully aware that modern lower courts often accept a mere showing of harm to the individual retailer (in the form of sales diverted from rivals to the favored purchaser) to satisfy this requirement, or allow plaintiffs to rely upon the Morton Salt inference to establish this harm to competition element with even less proof related to competition. Indeed, in my earlier post I acknowledge arguments that the allegedly unlawful discounts increase competition supported by proof the discounts result in lower prices, greater output, and a competitive response by retailers may well lose in district court.

But RPA defendants ought to make them for several reasons:

First, they are perfectly consistent with the RPA’s own language requiring a showing of harm to competition at the retailer level.

Second, they are consistent with the Supreme Court’s admonition in Reeder-Simco that even secondary-line cases are about “interbrand competition.”

Third, our methods for understanding the impact on competition from certain conduct have changed over time – and certainly since Morton Salt was decided in 1950. The RPA is a Clayton Act amendment and uses its terms, including “competition.” It is certainly relevant to show that the conduct alleged to harm or destroy competition actually enhances it if the term “competition” is to have its usual meaning within the antirust lexicon.

Fourth, in particular, evidence that the allegedly unlawful discounts provoke still MORE competition from rivals seems especially persuasive to me in showing the effect on competition is to intensify it rather than harm, reduce, or prevent it. This is precisely what Hausman & Leibtag find and I suspect would be a straightforward exercise for any economic expert to replicate with modern data. Helping the Article III judge to understand that this sort of evidence, properly understood, would exclude the interpretation that retail competition has been harmed requires less technical skill, but is an even more important skill.

Fifth, these cases are not terminating with district court rulings, no matter who wins. These are cases for the long game. I’d defend them as such. Appellate courts and especially the Supreme Court have shown significant willingness to entertain arguments and evidence that will harmonize secondary-line RPA cases with the rest of the antirust universe.

The next time an RPA advocate repeats the myth that there is no evidence RPA enforcement harms consumers, you will know not only why they are wrong, but also why it matters. The empirical evidence is not important because we need it to know RPA enforcement is bad for competition and consumers. Basic economic thinking suffices there. We need a sophisticated econometric evaluation of Walmart and other large retailers’ discounting practices to know the practice intensifies competition and benefits consumers about as much as we need a random control trial of jumping from an airplane without a parachute to know it is a bad idea.

The RPA has not yet had its GTE Sylvania moment. That watershed moment when the Courts bring the statute under the lodestar of the consumer welfare standard and harmonize it with the rest of the antitrust laws. But the Supreme Court has revealed its willingness to give it one. The FTC RPA agenda – specifically targeting markets where consumer benefits, in particular to low-income consumers, are enormous – may well accelerate that moment’s arrival. Empirical evidence that shows directly the magnitude of those benefits, that Walmart discounts increase competitive responses from rivals, and that the discounts enhance interbrand competition are important because they provide Article III courts the intellectual ammunition required to take the next step. RPA defendants must obviously color within the lines and offer defenses within RPA’s technical requirements as well. But the RPA’s GTE Sylvania moment will come by winning the broader battle of big ideas and doing so within the RPA framework.