Trump Antitrust, The Sequel

Welcome to the inaugural issue of Competition on the Merits! The election is coming. What might President Trump's second antitrust program look like? And why?

It is an election summer. And along with political debates, yard signs, and the suffocating heat (at least, in the DC metro area), it is also the season for rabid speculation about policy change. One need not eavesdrop in the halls of Congress or campaign war rooms to know that antitrust is the diamond of this election season.

One reason is that antitrust’s political salience increased dramatically since the 2016 and 2020 elections – in part thanks to the marketing success of the populist antitrust wings in both parties. We are up to more than 100 Wall Street Journal editorials covering Lina Khan’s FTC and its agenda and just as many fawning pieces from the antitrust trade press cheering on attempts to block mergers (“corporate greed!”) or bring Robinson-Patman Act claims to prohibit large discounts to large retailers (“equaling the playing field!”). Jonathan Kanter’s Antitrust Division has been just as active, if not a bit less of a darling of the Bloomberg’s and MLex’s of the world.

But even amid what appears—at least to most Americans—as bipartisan support for a rigorous antitrust enforcement, President Trump’s likely views on antitrust in a second term are not so easy to predict. They weren’t the first time around either. And the Republicans are in the middle of an important debate among themselves driven by competing visions about how conservatives should think about economic regulation generally, and antitrust specifically.

So for this inaugural issue of Competition on the Merits I am giving some thought to what I think President Trump’s antitrust policy might look like in a second term, what might be different this time, and identifying a few key unanswered questions. Hopefully the issue will mix a little bit of politics, a little bit of antitrust law and policy, and some economics. The plan is for future columns to follow this recipe — some in more academic form, some a bit less. Partially that is the plan because it is what I know. Partially it is the plan because more and more – modern antitrust policy is a complicated mix of all three ingredients: law, economics, and politics.

Let’s get started.

Trump Antitrust, Episode I: What Actually Happened Last Time?

Let’s start with what actually did happen in antitrust enforcement under President Trump the first time around. First, some general observations.

Hot Rhetoric. Many will remember the Trump administration came in relatively hot, at least in terms of antitrust rhetoric. And in a way not really seen before. Perhaps most famously, President Trump tweeted about his plan to challenge the proposed merger between AT&T and Time Warner. He called out individual firms – Amazon, various pharmaceutical companies, Apple and others. Some for reasons related to antitrust. Some found their way into the crosshairs for other reasons. Expectations were that the Trump administration would support a vigorous and robust antitrust enforcement program. And the bottom line is that the Trump administration did exactly that.

Fast (DOJ) and Slow (FTC) Appointments. The Trump administration moved quickly at the DOJ, appointing antitrust veteran Makan Delrahim as Assistant Attorney General. But it was much slower to fill vacancies at the FTC. Delrahim was announced as the nominee for Assistant Attorney General of the Antitrust Division in March 2017 and confirmed by September. The new FTC nominees were not even nominated until October 2017 and were not confirmed until May 2018.

The Trump FTC. In some ways, the FTC started off behind – with a lengthy lame duck period – and never really caught up for a number of reasons. The FTC faced dynamic, outspoken, and especially effective minority opposition from former Commissioner (now CFPB-head) Rohit Chopra. Chopra was an especially effective minority Commissioner. The FTC also had relatively weak majority leadership at the Chairman position in former Paul Weiss partner Joe Simons. Don’t get me wrong. Joe Simons was a fantastic antitrust lawyer with a distinguished record. And Simons’ dancing partners in the Commission Republican majority – former Congressional staffer Noah Phillips and antitrust lawyer Christine Wilson – were also strong voices at the Commission.

In typical years, that combination at the FTC would have been strong enough to carry a strong conservative majority during most of the modern FTC’s history. But 2017 to 2021 were not quite normal years in the political economy of antitrust. They were at the zenith of post-election conservative angst about the role of Big Tech in creating political bias and stifling conservative speech. Those concerns certainly persist — but the Elon Musk acquisition of Twitter, now X, and other developments have somewhat lowered the temperature from a blazing inferno to merely very hot. It was also the zenith, in my view, of the Neo-Brandeisian / Hipster Antitrust era. Progressive antitrust scholars like Carl Shapiro and Fiona Scott-Morton were turned upon harshly by a movement that outflanked them to the left. Lina Khan became a household name. Matt Stoller went from internet provocateur and troll to making lists of the most influential influencers among progressives. Proud Obama administration antitrust enforcers went from heroes of the progressive antitrust movement to being called corporate shills and betrayers of the “movement.” Well, that movement not only gained power now has a several year track record, for better or worse, and has generated ample reason for political opposition on the right from flouting the rule of law, abuse of the merger review process, disintegrating the reputational capital the FTC has acquired over decades, and imposing a woke social agenda in the guise of law enforcement.

The Trump FTC required unique leadership at a unique time. And while it had strong moments, Chairman Simons often took a position that emphasized political compromise and consensus over engaging in the knockdown, drag out fights that was often required. The virtues of bipartisan compromise at the FTC are not to be scoffed at. Indeed, Chairmen like Piitofsky, Muris, and Majoras helped to establish the FTC as a crown jewel of the administrative state. And at a time when that bipartisan compromise and stable enforcement policy for decades helped squirrel away reputational capital for the agency and save it from many political attacks.

But those were different ideas and a different time—a time where the gap in ideas between the most progressive and most conservative antitrust thinkers was far smaller than it had become by 2017 when the Trump administration took control. By 2017, three strong Republican Commissioners were needed for the fight with a rising and dynamic ideological opponent on the left as well as its own ideological tensions to resolve. And Chairman Simons’ understandable and even admirable propensity for compromise left Commissioners Wilson and Phillips one vote short a few too many times. For example, the Simons FTC was the first in the agency’s century-long history where a Republican Chairman formed a majority with his Democrat colleagues over the objection of every other Republican Commissioner. Suffice it to say that while the Trump FTC had its highlights, it certainly left some money on the table.

The Trump DOJ. The DOJ’s record was more consistent, as is to be expected because of the difference between executive agency antitrust enforcement versus an independent agency that must muster three votes for any action. It also generated a bit more controversy. But again, the overall record demonstrates a strong antitrust enforcement program under Makan Delrahim and one that, in my view, stands up even better after a few years. Let’s start with the best arguments against the Trump DOJ’s record.

The Antitrust Division faced significant scrutiny from the press and Democrat-led oversight committees for alleged controversies. Mostly, but not entirely, partisan concerns were raised about the President’s alleged “interference” in executive branch enforcement decisions, and in particular the AT&T / Time Warner challenge. Those concerns look a bit quaint years later with the tight link between the Biden White House and the FTC – a supposedly independent agency not under executive control. More generally, allegations of politically motivated antitrust enforcement under President Trump tend to ring hollow as the Biden FTC and DOJ target private equity, oil and gas, and Walmart, among others.

Criminal antitrust enforcement was down substantially during the Trump administration both in terms of cases filed as well as fines and penalties. Though the Trump DOJ did substantial work to extend its criminal enforcement program to labor markets, bringing the first criminal indictments for wage-fixing and no poach agreements. The Biden DOJ has picked on and continued this work.

In addition to administering an effective overall enforcement program – more on those numbers shortly – the Trump DOJ produced a number of lasting contributions that warrant singling out.

Perhaps the most significant and lasting contribution has been the Trump DOJ’s consistent defense of intellectual property rights. While many criticized the unusual circumstance of the DOJ filing a brief in the FTC’s case against Qualcomm (a case I wrote about here), it was part of a comprehensive program by the Antitrust Division to support the defense of intellectual property rights in federal court. The FTC’s Qualcomm case was very unusual because it was voted out at the very end of the Obama administration and made its way through the federal courts during the Trump administration. Normally, a new FTC would be able to put its stamp on the case once confirmed and decide whether they wanted to continue to pursue it, settle, or close the case. But because of the slow speed of FTC nominations after President Trump’s election, and a recusal from Chairman Simons that left the agency at a 2-2 stalemate, the FTC case against Qualcomm made its way through the federal courts without the Trump administration Commissioners having an opportunity to opine. The Trump DOJ’s brief (and later, Commissioner Wilson’s Wall Street Journal Op-Ed) are best understood as responses to those unusual circumstances.

Delrahim described his approach to IP rights as the “New Madison” approach, and spent a good deal of time and energy promoting it in federal courts. Students of law and economics might recognize the underlying tenets of that approach (e.g. “hold up” as a contract problem rather than an antitrust problem) as one that sounds in contract and property rights economics and the work of Ben Klein, Armen Alchian and others. My own work with Kobayashi in this vein was cited heavily by the Ninth Circuit in the Qualcomm decision. The Ninth Circuit’s adoption of this view is one of many examples of the lasting contribution the Trump DOJ’s Antitrust Division left by filing Statements of Interest in various federal courts advancing that approach with considerable success (see Delharim on these contributions here).

Less noticed was that the Trump DOJ brought more monopolization cases in 2020 than any administration since Nixon. And, for better or worse, it was the Trump DOJ that brought the Google search case soon heading to a decision. We will have time to write about that decision when it comes down. But again, this was a DOJ that was not afraid to bring difficult cases.

To be clear, I was a vocal critic of a handful of Trump DOJ enforcement decisions. I’m on the record predicting DOJ’s vertical merger challenge against AT&T / Time Warner would lose on the merits. And it did, primarily because it conceded in court that the transaction would generate hundreds of millions of dollars for consumers in the form of lower prices, but could not meet its burden to muster the economic evidence necessary to prove the transaction would harm consumers. I also criticized the FTC’s decisions, including its cases against 1-800 Contacts and Qualcomm, both of which were ultimately overturned. I also predicted the DOJ would lose the Googlesearch case. We will see how that one turns out. Reasonable minds can and often do disagree over the merits of complex antitrust cases, but the overall record for the Trump DOJ and FTC antitrust programs were quite strong.

That’s all well and good you say, but you read the NY Times and Bloomberg and Washington Post headlines and are quite sure the Khan and Kanter FTC and DOJ have a much stronger enforcement record. As a general matter, swings in non-merger enforcement can be misleading because they involve smaller numbers. Individual cases like the Google monopolization cases, or the FTC’s cases against Amazon or Meta, get a lot of attention. Small changes in non-merger enforcement activity can look more programmatic than they actually are. The most constant dimension of antitrust enforcement to evaluate across administrations is merger enforcement. The best place to start when thinking about what an antitrust enforcement program might look like under a second Trump administration is to evaluate the first one.

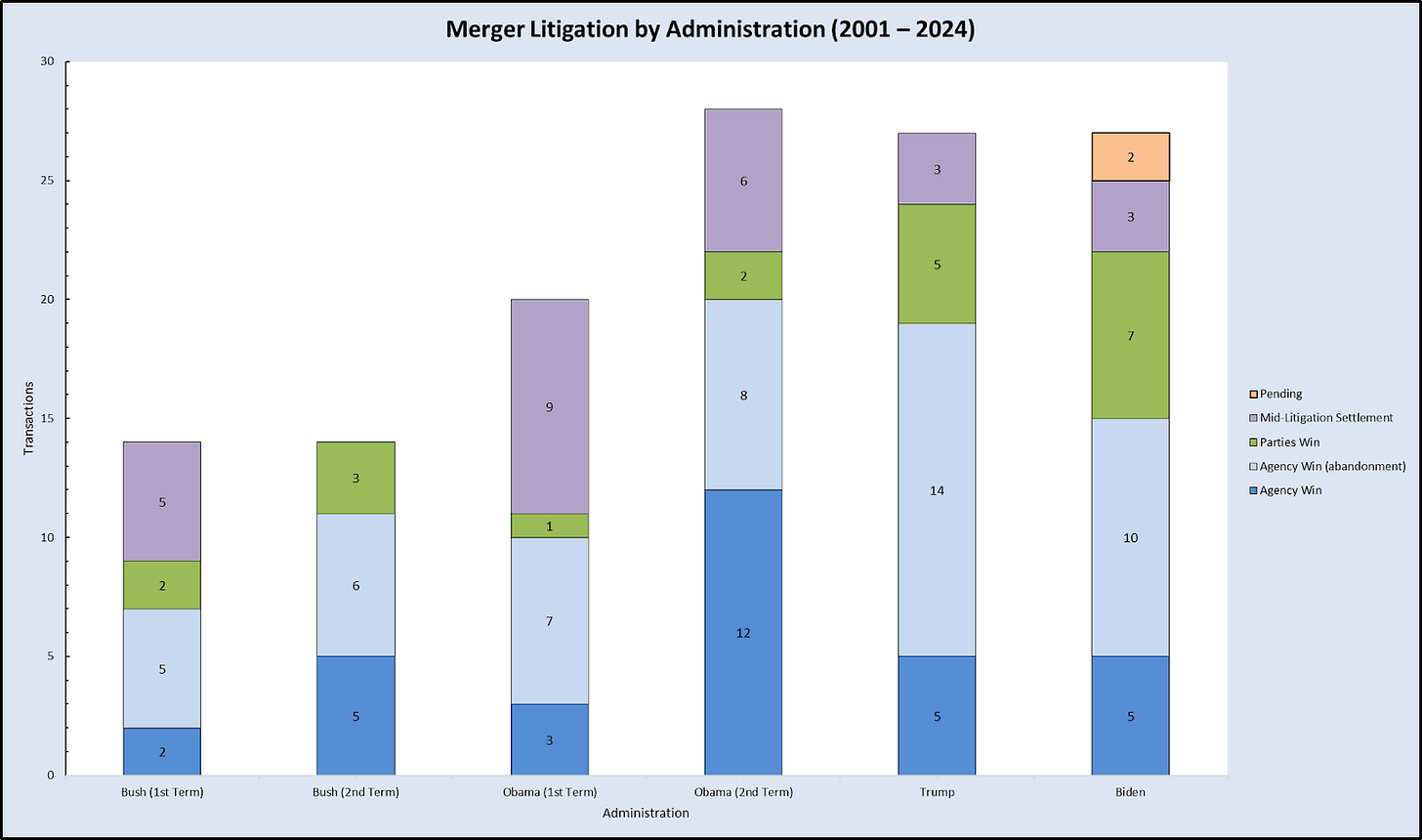

Here are relatively recent figures (the pending cases are FTC v. Tapestry/Capri and FTC v. Kroger/ Albertsons):

A good place to start is activity level. The Trump FTC and DOJ collectively challenged 27 mergers in 4 years. Compare that to 27 for the Biden administration in about 3.4 years or 42 in the Obama administration over 8 years. Controlling for HSR activity, the Trump administration and the Obama administration had similar enforcement rates.

How about losses in merger challenges? We can all agree losing is bad. The Trump administration had 5 litigation losses with 19 deals blocked or abandoned during its 4 years. Compare that to 6 losses for the Biden administration in just 3 years. If one includes both blocked mergers and transactions abandoned during investigation (the current FTC and DOJ press offices certainly count these as wins) that amounts to a merger win rate of 70%. That is higher than the Bush, Obama or Biden administrations.

If we look at the number of blocked transactions over time, we get a similar picture. Though the mainstream headlines are committed to a different narrative, the Trump antitrust agencies were as active (slightly more, even) as the Biden FTC and DOJ. The Trump agencies blocked 4.75 mergers per year compared to 4.71 merger blocks per year for the Biden administration. Compare that to the 3.25 mergers blocked per year during the Obama administration and 2.38 mergers blocked per year during the Bush years.

If we broaden the analysis to include all forms of agency influence on a deal (blocked, abandoned, or settled) we get a slightly different picture:

Bush 19.63 per year

Obama 25.88 per year

Trump 24.50 per year

Biden 12.94 per year

If one looks ahead, the Trump to Biden administration comparisons are likely to improve for the Trump administration. As the excellent Dechert DAMMIT Annual Report explains in great detail, 2023 merger enforcement fell off a cliff: “Only 12 significant merger investigations concluded in 2023—a drop of 40 percent from just last year and by far the lowest in DAMITT history. This observed and verifiable drop sharply contrasts with recent reports that Biden’s enforcers are setting new record highs for merger challenges.”

I don’t pretend these aggregated numbers and rates tell the full story of enforcement activity and outcomes. Some cases are tougher to win than others. Agencies can and have taken different approaches in terms of willingness to settle. And litigation skill is not constant across administrations either. But the numbers do help to dispel the misguided notion that the Trump FTC and DOJ were not active antitrust enforcers. Quite the contrary, the Trump administration holds up remarkably well in terms of activity level and well, winning.

Taking Stock

So that gives us an overview of what the Trump FTC and DOJ were up to the first time around. I think a few lessons stand out before we turn to what we might reasonably expect to change if we have a second Trump administration.

First, and to repeat, the Trump FTC and DOJ were active. Very active by historical standards. And they won. Commentary suggesting free passes for merger activity are misleading and overstated. Both the FTC and DOJ were very active in merger review but also willing to settle cases, which I suspect explains at least in part the poor Biden performance figures. The unwillingness to settle appears to be changing over time in the Biden administration. But the Trump administration was able to use settlements to solve competitive issues without litigation risk more effectively, and thus avoid losses in federal court. Complaints about procedural delays and tactics in the merger review process were also less prevalent during the Trump administration. There are of course other factors at play here. Some have criticized the FTC’s preparedness and litigation tactics and the House Judiciary Report suggests a serious disconnect between agency leadership and staff management when it comes to case selection and litigation.

Second, the Trump administration brought tough cases and was quite willing to litigate when necessary. They brought AT&T/ Time Warner. They brought the Google monopolization search case. I suspect a second Trump antitrust program would surely share the same willingness to bring hard cases.

Third, the Trump administration played offense on antitrust policy. From new Vertical Merger Guidelines to the DOJ’s Statement of Interest program to international competition advocacy defending intellectual property rights and the consumer welfare standard generally – the Trump administration’s antitrust agencies were active both in federal courts and international fora. Given the changes in the antitrust landscape in America and around the world in the intervening years I suspect this feature of a second Trump antitrust program would be even stronger. I’ll write more about international antitrust and competition advocacy later — but with increased concern about the FTC and DOJ colluding with the EU and other jurisdictions with regard to enforcement decisions, a general withdrawal from the United States in traditional advocacy for things like application of the consumer welfare standard abroad, and the “whole of government” approach domestically – suffice it to say that these issues will be attractive policy targets for a second Trump administration.

Trump Antitrust, the Sequel: What Has Changed and What Will Be Different?

What factors might influence the direction of a second Trump antitrust program? It is a useful exercise to think here about what has changed since 2020 in terms of the political economy of competition policy on the left and the right.

First, the political economy on the right has shifted in important ways since 2017 or even 2020. The debate on the right was and is often still caricatured as simply whether it is a good idea to weaponize the antitrust laws to target big tech. That characterization was incomplete even then, but it is both incomplete and obsolete now.

It is obsolete because a lot has happened. Namely, virtually every Big Tech target has been the subject of multiple antitrust suits by federal and state enforcers, even holding aside private litigation. Google has live suits targeting both its search and Ad Tech businesses, Amazon has been sued multiple times on competition and consumer protection grounds. DOJ brought a monopolization suit against Apple. Meta certainly has not escaped antitrust scrutiny. Big Tech is, frankly, up to its eyeballs in lawsuits, many which will not be resolved until well after the 2024 election. Heck, some may not be resolved by 2028. But it appears diminishing marginal returns for further large scale Big Tech antitrust suits have kicked in.

To be clear, I do not think the government will win many of those suits – perhaps the best shot is the Google Ad Tech case — but they will win something, or, at a minimum, extract settlements sufficient to declare a victory parade. The more salient point is that the Trump and Biden administrations already brought those suits. Of course there are ancillary suits an agency could bring, or future transactions to review and potentially block. But there just is not enough fresh meat on the bone to make “going after Big Tech” a core antitrust principle. Undoubtedly there will be well funded and influential players on the right that do now – and will still push for more here. And election season has a way of bringing the worst out of companies with a propensity for political bias and bad decisions. It is a season for unforced errors. But the main point is that the marginal benefit of weaponizing the antitrust laws to go after Big Tech is smaller because – well, it’s been done. By both sides. People on the left and right asking whether a second Trump term means “getting Big Tech” are fighting the political debate of 2016 or 2020 at best. But today’s debate is different. It is broader. And it requires conservatives to more firmly admit there are real tradeoffs between the perceived benefits of weaponizing antitrust today against one’s favorite targets on the one hand, and the real costs to Americans, to the economy, and to industry from an over-active approach to antitrust detached from the consumer welfare standard and constraints on the administrative state.

A more precise framing of the question even back in 2017 was whether the benefits of weaponizing the antitrust laws to target some of our most successful tech companies was worth the costs of undermining the rule of law. One such cost was the idea that when Democrats were in power they might use the same strategy to attack targets more friendly to conservatives. Another cost – the fraying of the rule of law – is more amorphous and hard to measure, yet very real to most conservatives who care about that sort of thing, myself included. Don’t get me wrong, the conservative complaints against Big Tech were serious ones: that they had acted in ways to actively support the Democrats or silence conservative voices. And there are many principled conservatives who answered the question “should we bear whatever costs come today or tomorrow for weaponizing antitrust against Big Tech firms in order to sanction those firms for perceived political wrongs?” in the affirmative. I’m friends with many of them and respect that view – even if I disagreed then and stand by that view now.

That more precise framing – “political targeting versus the rule of law” – is useful for drawing out a second important change: we’ve now had nearly a full term of the Biden antitrust. And to put it bluntly, the overreach has influenced conservative politics in antitrust in a significant way. Lina Khan and Jonathan Kanter have made it a political winner for the right to support the rule of law, the consumer welfare standard, and even got conservatives back to spending real intellectual energy and capital on questions like whether the FTC’s structure (and use of administrative litigation) are constitutionally sound! That is quite a feat in a short period of time. It was not long ago that Lina Khan secured 68 votes in the Senate for her confirmation as Commissioner.

Back in 2020, people like me were standing up in rooms saying “Be careful about giving the FTC or DOJ more power in the name of punishing Big Tech because they are going to use it to go after everyone.” To Chair Khan and AAG Kanter’s credit, this was their message too. They were not hiding it. And boy have they done exactly what they said:

Merger review has become exponentially more difficult for even mundane transactions;

The withdrawal of the Trump administration Vertical Merger Guidelines and the introduction of the new, more structural, and less economically sound Merger Guidelines

Throwing away the bipartisan Section 5 Policy Statement that harmonized the FTC’s unfair methods of competition authority with the rest of the federal antitrust laws under the consumer welfare standard;

New proposed HSR rules threaten to raise the costs of M&A activity for all firms;

The broad sweeping non-compete rule flouts any reasonable interpretation of the FTC Act – triggering concerns about overreach by the administrative state among all kinds of conservatives – not to mention trashing a century of state law governing the practice;

The new Robinson-Patman Act enforcement push targets Walmart, Costco, Target, Coca-Cola, and Kraft Heinz, among others – and punishes them for practices well understood to result in lower prices to consumers and;

The FTC has gone out of its way to flout the rule of law to target private equity and oil and gas mergers (as well as individual executives, like former Pioneer CEO Scott Sheffield, in its recent settlement in the Exxon / Pioneer matter)

These are just a handful of examples. And does not even include the serious concerns about agency morale and mismanagement highlighted by the very thorough House Judiciary Report.

The long and short of it is that the political economy has changed. Big Tech will undoubtedly still be a popular target on the right. But the landscape is broader now. The happenings over the past four years have made other priorities and objectives at least as important. Oil and gas companies like Exxon; popular retailers like Walmart, Costco, and Tractor Supply; beloved brands like Coca-Cola and Kraft Heinz; airlines; and private equity have all been targets of the Biden administration. Expect a good deal of conservative thinking and political energy and capital around competition issues to be dedicated to new priorities – which are going to sound familiar to some of you who have been around this space for awhile:

Assessing the constitutionality of administrative adjudication and rulemaking at the FTC

Reharmonizing enforcement under Section 5 of the FTC Act with the traditional antitrust laws

Considering whether OIRA should govern independent agencies (a pet project of former Trump OIRA Administrator and now D.C. Circuit Judge Neomi Rao)

Reforming the HSR process to be less burdensome

Reforming or repealing the Robinson-Patman Act

Getting back to International Competition Advocacy

I do not expect by any stretch of the imagination, and would not predict, a Trump antitrust regime that looks like the Bush administrations or one that has a uniformly laissez-faire bent. Not at all. I would expect aggressive, targeted, and principled enforcement – including at least some aimed at Big Tech. But I also expect a Trump administration that is very attuned to the overreach of the Biden administration and the political and economic benefits of cutting back on those excesses. It is a difficult and complicated balance, both politically and in the execution of policy. But one can already see signs of President Trump recognizing the benefits of campaigning against overregulation now – for example, in his recent speech to the Business Roundtable. President Trump’s willingness and desire for an aggressive antitrust enforcement arm will be there, just as it was during his first term, but expect to see more give and take between a distinct focus on regulatory cleanup and eliminating bureaucratic costs and barriers, and aggressive enforcement. I wouldn’t expect either of these forces to dominate, but rather a balance between the two and, importantly, personnel choices attuned to the tradeoffs.

There will be plenty of time to discuss these and related issues as we get closer to November. Keep your seatbelt on, dear readers.