What Kind of Animal Is the FTC's Platform Censorship RFI? Competition, Consumer Protection, or Both?

Unless it uncovers evidence of collusion on policies among platforms (and it might), there is good reason to doubt the RFI leads to antitrust cases. Consumer protection on the other hand, I'm buying.

Welcome back to Competition on the Merits.

Last month, FTC Chairman announced a major policy initiative in the form of a Request for Information (RFI) “to better understand how technology platforms deny or degrade users’ access to services based on the content of their speech or affiliations, and how this conduct may have violated the law.” Today’s Competition on the Merits is about answering the question: “If platforms’ content moderation decisions did violate the law — which law would it be?” Antitrust? Consumer Protection? Both? Neither?

What kind of animal is the Technology Platform RFI?

Much has been said– favorable and unfavorable – about Chairman Ferguson’s Big Tech Censorship RFI, ranging from applauding the public inquiry to criticizing it as a frontal assault on free speech. Dan Gilman at Truth on the Market provides characteristically insightful and reasonable analysis. One thing that cannot be said is that the Big Tech Censorship RFI is any kind of surprise. President Trump, Chairman Ferguson, and FTC Commissioner Holyoak have been consistent about concerns regarding content moderation and editorial decisions made by social media companies (in particular) that impact certain perspectives.

In a recent interview, Chairman Ferguson described the FTC’s job as one of a cop on the beat rather than as a regulator. With that in mind – what sorts of violations of antitrust law or consumer protection law could the Big Tech Censorship RFI be aimed at? There are several possibilities.

The RFI itself begins to catalogs them:

Commissioner Holyoak’s speech on the topic elaborates upon some of the consumer protection links to content moderation and platforming decisions:

Chairman (then Commissioner) Ferguson’s concurring statement in the FTC’s GOAT settlement emphasizes that the antitrust laws too may play a role in the event of coordinated action among platforms:

For those keeping score at home, let’s break this down a bit further into antitrust and consumer protection legal theories involving content moderation, platforming decisions, or terms of service:

Denial or degrading service to particular users based upon the content of the users’ speech or their affiliations;

Failure to disclose material terms involving the platform decision to dismiss or downgrade a users’ access;

Violation of a platform’s own terms of service or other policies flouting users’ reasonable expectations based upon the platform’s public representations;

Unilateral content moderation decisions made by tech platforms with market power;

Collusion among competitors on censorship or content moderation policies; and

Collusion among competitors in the form of advertiser boycotts, as in the alleged boycott facilitated by GARM of the X platform.

The first three are consumer protection related theories – either under the FTC’s deception or unfairness authorities. The second three are antitrust theories of harm alleging either unilateral or collusive conduct.

Back to our animal classification exercise. Let me say a bit more about what I mean. Large scale sectoral investigations – which is really what this is – come in many different shapes and sizes. And they have different outcomes. Some sectoral inquiries never become more than that. Public investigations are announced. Comments sought. White papers may even be drafted. But we do not see legal action. Sometimes we see useful policy reports or information-gathering. But no enforcement actions. That is one possibility.

To be clear, I do not mean that as a criticism of those sectoral inquiries that remain about information gathering and do not result in any enforcement action. The topic of platform content moderation decisions and platforming choices are incredibly important to a large number of Americans. The FTC’s website has already received more than 1,000 comments on the RFI. Learning about practices that are important but largely opaque from users would be an important contribution in its own right and well within the powers granted to the FTC under Section 6b of the FTC Act. In short, the Censorship RFI is both a legal and productive use of the FTCs resources.

But let me also discard that possibility right off the bat. I do not doubt for a second that we are going to see the FTC bring cases consistent with the legal theories hinted at in the RFI. Between Chairman Ferguson and Commissioner Holyoak’s own comments on the subject, and the President’s enthusiasm on the same, this is going to be more than a bullet by the ear.

The question for the day is whether the FTC Big Tech Censorship RFI is going to turn into antitrust enforcement, consumer protection enforcement, or both? Again, what kind of animal will it be?

If the practices are illegal, what laws are they most likely to violate? I think the likely answer is that the Big Tech Censorship RFI and subsequent information gathering investigation turns into a consumer protection animal. Perhaps exclusively so.

Today’s COTM explains why that is the case. First, I’ll briefly discuss some leading antitrust theories concerning platform content moderation decisions and some of the substantive roadblocks those theories face. The punchline will be that in the absence of very specific findings of explicit collusion among tech companies on content moderation policies, any antitrust claim sounding in unilateral content moderation decisions is likely to fail at the motion to dismiss stage. Of course, perhaps such evidence exists. That’s what investigations are for after all. And maybe the FTC will find such an agreement. But the FTC will need it to have a real chance at prevailing on any of the antitrust claims.

Second, I’ll turn to the consumer protection theories – which, in my view, seem to face fewer serious legal impediments to success and appear to provide a more promising path for enforcement actions related to the RFI (accepting the caveat of evidence of an explicit collusive agreement among social media platforms on the content of content moderation policies or terms of service).

Antitrust Law Imposes Its Own Limits Upon Theories of Harm Related to Speech

Let’s start examining a handful of antitrust theories of harm related to platform content moderation policies. Again, let’s hold aside express collusion on content moderation policies or terms of service. And this is not a trivial caveat. Those would be real cases. And you can bet the FTC will be looking hard for an actual agreement along these lines. Chairman Ferguson argues the possibility of such collusion is not far-fetched at all in his concurring statement in the FTC’s GOAT settlement. He argues there that because discovery in Missouri v. Murthy revealed significant collaboration between the federal government and multiple platforms on content moderation policies we should not be surprised to find coordination among the platforms themselves. In his own words:

Fair enough. It is absolutely right that explicit collusion would give rise to a viable antitrust claim against social media firms or advertisers coordinating a boycott. And maybe they will find that. Question 5e and Question 6 in the RFI targets directly the issue:

So take my caveat holding aside explicit collusion theories with a grain of salt. Perhaps I’m assuming away all the real action. But I do not think so. The Censorship RFI itself and other statements from Chairman Ferguson and Commissioner Holyoak suggest FTC interest in other antitrust theories. It is these unilateral theories of antitrust harm I think are likely dead ends under any reasonable reading of modern antitrust law. Let’s briefly work our way through those theories at a high level. And again, my focus will be antitrust law’s limits on these theories of harm. Obviously the First Amendment has something to say here as well! But I think we can show the limitations on the reach of antitrust law even staying within its bounds.

Unilateral Antitrust / Content Moderation Theory #1: Censorship As An Indicator of Market Power

The basic idea here is that only a firm with market power can profitably deplatform a large fraction of its users, or degrade product quality. The stronger form of this argument is that a platform that pushes away a large fraction of its user base is actually reducing its output (of course, we can debate how to measure a platform’s output). But you get the idea. And you do not have to search hard to find someone making it. Here is Commissioner Holyoak in a recent speech:

Of course, it may or may not be true that evidence of censorship or content moderation supports an inference of monopoly power. But let’s set the terms of debate. Is censorship a sufficient condition for evidence of monopoly power? I don’t think so. We can think of all sorts of business owners without any form of monopoly power or control over market conditions who choose to exclude some patrons from accessing their services (“No shoes, no shirt, no service,” etc.). Property rights are a sufficient condition for some form of exclusion – after all, that is the point of property rights. But they do not all confer monopoly power. Overly simplistic? Yes. Are social media platforms different than other businesses? Sure. They are larger than most. And some arguably have quite large market shares – though competition seems to be on the rise rather than the decline. Still. Hold aside those distinctions for a minute and just zoom in on the antitrust question of whether the observation of censorship or content moderation is a sufficient condition for proof of monopoly power from an antitrust perspective. The answer to that question is no.

Now, that is a different question from whether social media platforms actually have market power. And if so, which ones? Does Google have market power in search? Absolutely. And could evidence of a profitable degradation of quality (through content moderation) be used to show monopoly power? Yes. It could be very relevant. But whether you call it censorship, editorial discretion, or deplatforming, the fact alone is not dispositive.

Still, that is not even the really important question here for antitrust law. The antitrust laws do not condemn the possession of monopoly power alone. This is antitrust law 101. Lawful acquisition of monopoly power is something that distinguishes American antitrust law from most of the rest of the world. And it is a very good thing that is the case.

As I’ve written elsewhere: “if the consumer welfare standard is king, Trinko is prince,” referring to the precedent that protects American firms that innovate and earn a monopoly position through a superior product from being turned on by regulatory agencies for violating the antitrust laws. What does Trinko say?

"The mere possession of monopoly power, and the concomitant charging of monopoly prices, is not only not unlawful; it is an important element of the free-market system."

This is a simple, and powerful principle. Be they Neo-Brandeisian or progressive or conservatives who desire to weaponize antitrust against large tech firms, demand to undo this core feature of American antitrust law runs high. See, for example, Lina Khan’s calls to reverse Trinko in her role in producing the Democratic’s House Report.

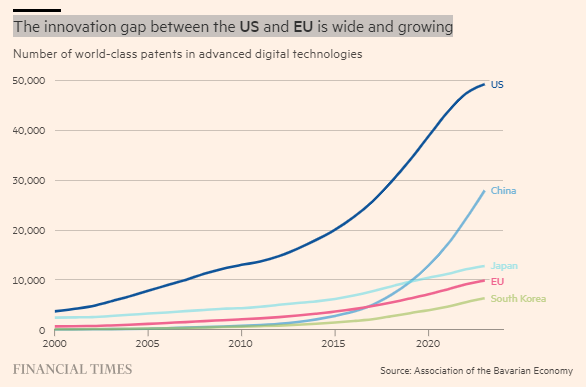

The road to the Europeanization of American antitrust and with it, the American economy, begins with undermining the consumer welfare standard. And undermining the consumer welfare standard starts with weakening Trinko. It is as simple as that. And Trinko, in turn, is at least partially responsible for this:

I’ll get off of the Trinko soapbox, for now, to return to a doctrinal point. Let’s presume that censorship from a large social media platform does suggest evidence of market power. The right doctrinal answer is: “So what? Market power alone does not violate the antitrust laws.”

Now there are plenty of good rebuttals. For one, the FTC is well within its statutory mission to understand conduct and anticompetitive effects even if they do not violate the law. High prices sometimes (even often!) do not violate the antitrust laws. But it is a good idea to study them sometimes. The same can be said for various aspects of quality, including content moderation policies on social media platforms.

But notice that explanation is an explanation for why a sectoral inquiry might make sense and prove to be a productive expenditure of resources for a competition agency. It is not an explanation of a path to antitrust law enforcement. The bottom line is that American antitrust law distinguishes itself from Europe and China by allowing firms that innovate and outcompete rivals to charge the monopoly price as a reward. As a plain black letter law corollary of that principle, it does not violate the antitrust laws for a social media firm with market power to raise price, reduce quality, or even to reduce output. You can argue about whether that is a good thing or not. But it is the law.

Unilateral Antitrust / Content Moderation Theory #2: Content Moderation is a Form of Quality and a Decision to Degrade Quality Generates Anticompetitive Effects

A related antitrust theory of harm we can dismiss briefly because it is really the same as the one we’ve already discussed, is that a single firm imposing content moderation policies that deplatform users or deprive access is reducing quality or reducing output. Again, for the reasons already explained, the answer is: “So what? American antitrust law gives single firms the right to raise price, reduce output, or reduce quality in the ways they see fit.”

Again, there are exceptions to this rule. A social media platform with market power cannot engage in collusive conduct. Conduct that excludes rival platforms from competing with it can also give rise to antitrust liability. But unilateral theories of harm based upon content moderation policies affecting users are not likely to generate antitrust liability under existing law. And again, that is not even getting to the First Amendment issues – which are significant. Here is SCOTUS in NetChoice v Moody:

But I will leave others to examine those First Amendment arguments more closely. For our purposes – it suffices to point out that EVEN if it were true that a social media firm with monopoly power decided to reduce quality (via content moderation or otherwise) or reduce output, that alone would not suggest an antitrust violation nor could it undergird a related theory of antitrust harm.

Doesn’t that mean that the antitrust laws allow for some anticompetitive effects? Yes. Absolutely. The antitrust laws do not put agencies or courts in the position to serve as price regulators, much less output or quality regulators. The antitrust laws are about competition as a whole. And when a firm becomes a monopolist by attracting consumers and users through a better product – the antitrust laws give them a wide berth to design their product and make price and output decisions. That is not a free hall pass to violate the antitrust laws! But antitrust theories of harm are limited to conduct that impacts competitive conditions, they do not allow for second-guessing the price, output, or quality decisions of a firm that has achieved its market power lawfully.

Once again, a worthy subject of study. And perhaps the FTC uncovers evidence of collusion or exclusion. But in the absence of that evidence this popular theory of antitrust harm is likely a dead end.

Unilateral Antitrust / Content Moderation Theory #3: Contractual Opportunism by the Platform In the Form Of Changing Content Moderation Policies After Users’ Adopt the Platform

A slightly less popular theory of antitrust harm related to content moderation is what I will describe as the “hold up” or opportunism theory. Antitrust readers who followed the patent holdup debates of the last couple of decades will understand the reference.

In the patent context, the underlying antitrust theory that has seen very limited (but non-zero) success goes as follows: (1) a standard-essential patent holder deceives a standard setting organization (SSO) by failing to disclose its patent or falsely denying having a patent that reads on the standard; (2) the SSO adopts the SEP holders’ patented technology into the standard; (3) the SEP waits quietly while firms adopt the standard and make products using the technology; and (4) once the standard is adopted, the SEP holder jumps out demands supra-competitive royalties (even if it has agreed not to charge them) or it enjoins production of products using its technology. For those interested, everything you wanted to know about the antitrust law and economics of patent hold up is in this paper with Bruce Kobayashi.

The FTC fell in love with attacking so-called “patent holdup” using the antitrust laws in the 1990s through the 2010s. The pursuit did not go very well. But it was not without its wins. The FTC entered into a handful of consents that suggested that a patent holder that deceived the SSO could be in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act’s prohibition on Unfair Methods of Competition. It tried to extend that to cases where the SEP holder did not deceive anyone but changed contract terms to increase royalty rates over the life of the license. That project largely failed. No federal court has endorsed that theory. The deception theory has a famous loss in FTC v. Rambus in front of the D.C. Circuit. Again – go read the Kobayashi & Wright article if you’re interested in this topic. But I will try to be brief here. In Rambus, the D.C. Circuit very importantly held that if the SEP holder acquired its market power lawfully, its conduct was largely protected under the antitrust laws and it would only be liable if the FTC could prove that, but for its deceptive conduct, the SSO would have adopted a different technology. Merely showing Rambus was able to get better prices was not actionable. (This is the Trinko principle discussed above).

What does that have to do with social media platform censorship? Perhaps nothing. But perhaps something. The RFI appears to be getting at a Rambus-like theory of harm. Here’s Question 6d:

The idea would be that the platform is able to achieve dominance under the permissive policy, attract users to the platform, and then “hold up” the user base once they are on board by imposing a lower quality policy once it was difficult for users to switch platforms. I have not studied closely the evidence on changes in these policies over time. I suspect that most of the changes in policies or conduct that concerns the FTC took place long after any of the relevant social media platforms acquired market power. Though perhaps that is not correct.

What I do know is that an antitrust hold-up theory here would be quite difficult and would require the FTC, under Rambus, to show: (1) the platform has monopoly power; (2) the platform deceived users by knowingly misleading them about platform policies, i.e. the change from the permissive policy to the harsher one had to be something the platform knew it going to do ex ante; and (3) but-for the the platform’s deception, users would have gone to a different platform.

Not impossible. But perhaps close to it. And at a minimum, a tough case to bring and win under existing law. There is always the possibility of a Section 5 Unfair Methods of Competition (Section 5 UMC) claim which brings with it a lower burden of proof. But that also has its own downsides in terms of remedies and litigation risk. We will discuss Section 5 UMC soon enough.

To be clear, none of this means the RFI is a waste of time. Quite the contrary, examining practices and competitive outcomes in industries that affect a lot of consumers is precisely something worth studying for the FTC. For example, the FTC of the 1990s and 2000s spent a lot of time studying industries and practices that had significant immunity from antitrust enforcement (e.g., alcoholic beverages) and contributed greatly to the policy discussion. Uncovering content moderation practices and discrimination against particular groups or perspectives is a useful exercise and can inform policy. It can also inform users about what is happening on various platforms so that the users can make decisions with full information. And it can report on what it finds to Congress and others.

But – again, notwithstanding the uncovering of evidence of express collusion – I would bet the under that a court ever finds an antitrust violation related to conduct discovered in the RFI inquiry. Because of that, I am skeptical the FTC is likely to bring a non-collusion based antitrust case here. So if the Censorship RFI is not likely to generate an antitrust enforcement agenda or set of cases, what kind of animal will it become?

The Platform Censorship RFI as a Consumer Protection Investigation

If you have stayed with me this long – here is the punchline. The Censorship RFI walks and talks to me like a consumer protection project. And a potentially fruitful one at that. As discussed, I am short on its long-term value as the basis for antitrust enforcement. But as a foundation for actions against platforms related to content moderation policies using the FTC’s core consumer protection authorities? I’m buying.

Recall that the FTC has two basic consumer protection authorities: Deception and Unfairness. Deception applies to misrepresentations and omissions of material information that leaves consumers worse off. The FTC’s unfairness authority extends to acts or practices that harm consumers and are not justified by benefits to consumers or competition.

Let’s start with the RFI itself. You can read it here. The very first question is framed as an unfairness inquiry under the FTC’s consumer protection authority:

The question is searching for identification of conduct that negatively affects users and is not justified by “countervailing benefits to consumers or competition.” The question tracks precisely the language of the unfairness standard and is an invitation for conduct that might satisfy that standard. What sort of conduct? Again, unfairness inquiries will be limited by the First Amendment. Moody v. Netchoice protects choices by the platforms that are related to their ability to produce an “expressive product.” The fruitful path for the FTC’s unfairness authority would appear limited to conduct that does not relate to the ability of the platform to offer an “expressive product.” That might be a narrow needle to thread. But it is not an empty set.

For example, the FTC has used its unfairness authority to bring cases where companies did not do enough to protect users’ privacy, information, or to protect them from fraud or some other sort of harm. In those cases, the FTC challenged the procedures and safeguards the company had in place to protect their own users – usually arguing that the risk to consumers (from e.g., lack of security to prevent a data breach) is significantly greater than any cost to the company to mitigate that risk. With that in mind – read RFI Question 3, focused on the platform’s processes and safeguards against deplatforming:

And read that in conjunction with Question 4, focusing on the harm to users arising from adverse action:

Read together, RFI Questions 3 and 4 are aiming directly at searching for unfairness cases alleging the platforms’ internal procedures exposed users to the risk of deplatforming and its negative consequences unnecessarily. This is an attempt to focus on platform internal procedures rather than the “expressive product” protected under Moody.

The most fruitful path appears to be the FTC’s deception authority. And the RFI targets deception as well. Here’s Question 2:

Question 2 focuses on deception. Of course, the First Amendment does not protect platforms from deceptive (and material) statements that are relied upon by consumers to their detriment. Question 2 asks to collect public-facing representations and will undoubtedly be followed up upon with an examination of whether those statements were adhered to by platforms, when they were not, reliance on those statements by users, and harm to consumers arising from failing to follow policy statements or terms of service.

For my money, the deception authority seems to be the highest rate of return enforcement vehicle for the FTC’s RFI aimed at social media platforms’ content moderation policies. The deception authority is limited to statements the platforms’ actually made about their own policies (as well as their terms of service). And the FTC certainly would have to show those statements were material to users. This can be a challenge with online statements. On the other hand, the deception authority avoids the problems discussed with antitrust theories, applies to unilateral conduct, and – compared to unfairness – does not allow defenses that the platform adopted the policy at issue to benefit consumers or competition.

There will be much more to say about the RFI and the FTC’s agenda with social media platforms. But I thought it would be fun and informative to lay out some of the differences between the antitrust and consumer protection related theories of harm hinted at in the RFI. Best I can tell, and where I will leave you for today dear readers, is that the most likely outcome of the RFI and the FTC’s content moderation and censorship agenda more broadly, is an aggressive investigation and enforcement that sounds in Section 5 of the FTC Act and the FTC’s consumer protection authorities.

As always, please subscribe, upgrade to paid, and send to your friends! See you soon.

Given comment (quickly withdrawn under pressure) by FTC lawyer asking for delay in Amazon case due to shortage of resources , opening an inquiry into social media censorship, seems way down the list of FTC priorities https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2025/03/12/tech/ftc-amazon-trial-musk