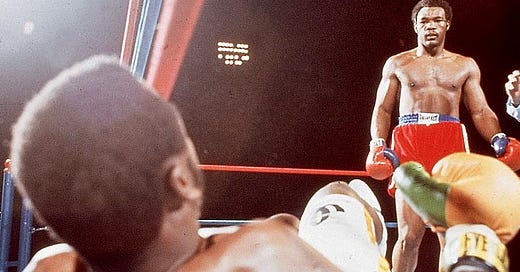

Down Goes Humphrey's Executor! So What Happens Now?

Humphrey's Executor, the long embattled precedent limiting the President's ability to fire FTC Commissioners, is dead.* I explain the practical implications for the FTC & lawyers dealing with it.

Welcome back Competition on the Merits readers.

It has been quite the week. The FTC dropped one of its pair of Robinson-Patman Act cases. The suit against Pepsi is dismissed. As predicted. The RPA claim against Southern Glazer’s remains. For now. The RPA revival is on life support. But it is not dead. Statements of interest in its potential future enforcement from Chairman Ferguson and Commissioner Meador keep it alive for now. What does that all mean and what happens next? We will turn to that next time.

This week’s COTM takes on a bigger issue. At least as measured by symbolic value rather than economic value. Humphrey’s Executor – the long embattled Supreme Court precedent that declared constitutional limitations on the President’s removal power over FTC Commissioners – is dead.* Dead enough, anyway. For over 90 years, Humphrey’s Executor has stood – at least to conservatives – as a symbol of much of what has gone wrong with the administrative state: unfettered expansion, mission creep, regulatory capture, and malfeasance allowed to thrive without answer or accountability. Now, its execution date has been set. Plenty has been written about Humphrey’s Executor, agency independence, and the separation of powers.

Indeed, I covered the inevitable fall of Humphrey’s Executor here at COTM when it appeared that former Chair Khan rather than Commissioners Bedoya and Slaughter might be on the receiving end of removal. The prediction below was fairly prescient – right analysis, wrong Commissioners.

But I want to focus today’s Competition on the Merits not on high theory and implications for separation of powers or the administrative state, but rather on what the fall of Humphrey’s Executor and agency independence means for the Federal Trade Commission as a practical matter.

What will it matter for cases? How might the end of tenure protections for Commissioners impact agency performance and decision-making? How will it impact the FTC’s unique role as an expert agency that also carries out administrative adjudication? Does more executive branch control over the FTC mean Congressional oversight? Does the end of removal protection mean the eventual end of the FTC?

Let’s get started. And as always, please subscribe, upgrade to paid, and send to friends. I should have some news shortly about extra content for paid subscribers. Stay tuned for that.

Trump v. Wilcox: Down Goes Humphrey’s Executor!

Let’s get up to speed. Just a few days ago, the Supreme Court granted a stay of an injunction granted by the District Court for the District of Columbia in Trump v. Wilcox, the lawsuit in which Gwynne Wilcox and Cathy Harris challenged their removal as members by President Trump from the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), respectively. In a 6-3 decision granting the stay, the Supreme Court held quite plainly: “because the Constitution vests the executive power in the President, Art. II, §1, cl. 1, he may remove without cause executive officers who exercise that power on his behalf, subject to narrow exceptions recognized by our precedents, see Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 591 U. S. 197, 215−218 (2020).”

This is not the full decision on the merits. The Supreme Court majority reserved and did “not ultimately decide in this posture whether the NLRB or MSPB falls within such a recognized exception” to the general rule that the President can remove officers who exercise that power on his behalf. The question will receive full briefing and argument. But this decision to grant the Government’s request for a stay is more than just the writing on the wall. Humphrey’s Executor remains alive in theory, but not in practice, given only a temporary reprieve until the final decision in Wilcox is formally rendered.

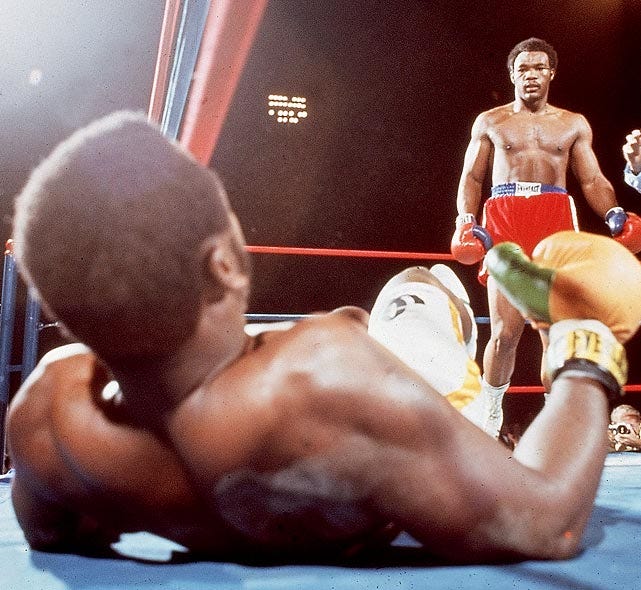

Of course, Trump v. Wilcox is not the only game in town for Humphrey’s Executor. Former Commissioners Alvaro Bedoya and Rebecca Slaughter filed suit after their own termination by President Trump in March. Slaughter v. Trump is winding its own way through the federal courts with motions for summary judgment (in each direction) argued last week and taken under advisement. The Supreme Court’s emergency docket decision in Trump v. Wilcox portends the end of the exiled Commissioners’ bid to return to the FTC.

The death of Humphrey’s Executor was – and remains – inevitable. Its days as good law are now finite and approaching zero. And while it remains to be seen whether it is the NLRB or the FTC litigation that winds its way through the appellate process first, those are now just details for administrative law casebook authors to fret over. Humphrey’s Executor will be overturned. Removal protections for members of multi-member commissions carrying out executive power will come to an end. And Section 1 of the FTC Act, which limits the ability of the President to remove a Commissioner but for reasons of “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance,” will no longer be the law of the land at the FTC. Presidents will be able to fire Commissioners for any reason.

There has been quite a bit of pearl clutching and hyperbole about that possibility and what it means for the FTC. On the one hand, defenders of Humphrey’s Executor and removal protections have declared that its reversal portends the end of the FTC’s enforcement mission and akin to facilitating fraud? Give me a break.

The former Commissioners-in-exile have repeated the theme that shifting regulatory authority from a for-cause to at-will system under the executive branch will mean the end of regulation.

There are strawmen on both sides of the debate, of course. Defenders of the unitary executive and those who cheer on the fall of Humphrey’s Executor – to be clear, I count myself as squarely within this group – sometimes incorrectly argue that without unfettered removal power the President has no tools at his disposal to reign in an otherwise unaccountable regulatory agency. That is certainly not the case, as we will discuss.

However, the truth of the matter is that despite those alternative instruments of Presidential control over the FTC – namely, the ability to designate the Chairman from sitting Commissioners and to propose a budget to Congress – the growing body of evidence shows that the FTC has long been behaving like an executive agency. Indeed, I’ve made the case elsewhere that the three distinctive features of the FTC relative to its executive counterpart (the DOJ Antitrust Division) – that is, Section 5 Unfair Methods of Competition authority, administrative litigation, and 6(b) research studies – have been abused for partisan ends for years if not decades.

But today is not a column about whether or not the President should be permitted to remove FTC Commissioners, though I answer that question in the affirmative. Today is about what it means for the FTC that President Trump and future Presidents will have that ability. What changes in FTC enforcement? What practical impact will it have, if any, in the short to medium run? Does removal power make it more likely the FTC is not around in the future?

What follows are ten implications of Presidential removal power at the FTC. Let’s start with a few big ticket items.

1. The FTC Is Unlikely to Continue as a Bipartisan Commission

First things first. With the Democratic Commissioners removed, a frequently asked question is whether the President must replace Bedoya and Slaughter with new Democratic nominees? The answer is “no.”

To begin with, the FTC Act does not require the agency to have either Republicans or Democrats in the two minority seats. The statute only requires “Not more than three of the Commissioners shall be members of the same political party.” This is commonly misunderstood because historical practice has largely been full commissions with three members of the President’s party and two from the minority party. But that is not required by the FTC Act. A President who felt compelled to have all five Commission seats filled could, lawfully, nominate and confirm 3 members of his own party and two independents (presumably, with views that aligned with his own). In short, President Trump’s removal of Commissioners Bedoya and Slaughter does not require him to replace them with two Democrats. Not doing so would be a break with historical practice, but not the FTC Act.

But is the President compelled to replace the removed Commissioners at all? I do not think so. While the FTC Act says that the FTC “shall” be composed of five Commissioners, the FTC Act contemplates vacancies and explicitly notes that “a vacancy in the Commission shall not impair the right of the remaining Commissioners to exercise all the powers of the Commission.” Certainly, the FTC has gone long periods of time operating without a full slate of Commissioners, including lengthy stints with as few as two Commissioners.

For now, the FTC is going to continue as a Republican-only operation. And I suspect, when a Democrat sits in the White House, the FTC will operate with only Democratic Commissioners. This does raise some thorny issues in transitions. For example, if a Democrat wins the next presidential election and all Republicans resign on or before January 20, 2029, who will run the FTC until new Democratic Commissioners are confirmed? That issue is solved with “Acting” officers at the DOJ. And I presume that a similar arrangement will be made at the FTC when the time comes. But the days of a multi-member, bipartisan FTC are over, at least for now.

2. The President Has Always Had Some Control over the FTC – Now He Has More

Overturning Humphrey’s Executor is correctly thought of as giving the executive branch more control of federal agencies on the margin, but it always had some control. We should think about this as a move along a spectrum rather than a binary change. The White House has some pressure to bring to bear on the FTC independent of the threat of removal. For example, the President submits the FTC budget to Congress and gets to choose the FTC’s Chairman among the sitting Commissioners. The White House always has had the ability to prevent FTC Commissioners from acting in their official capacity overseas. On top of all of that, as we’ve discussed, President Trump’s recent executive orders also give the White House additional control over the FTC and other federal agencies by putting them under OIRA and OMB supervision.

I would not forget about those instruments of control over FTC Commissioners. Removal takes time. It can be costly in the sense of expenditures on political capital both to remove and to nominate and replace new Commissioners. Overturning Humphrey’s Executor adds a blunt and powerful hammer to a toolkit that already included plenty of smaller tools.

3. Will Congress and the President Play Tug-o-War Over the FTC?

Both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue exercise some control over the FTC. Congress has traditional tools of oversight and appropriation. Students of the FTC’s history understand this well. In various periods of FTC overreach – particularly during the 1970s – it was Congress not the White House who threatened to end the FTC. During more recent abuse during the Khan FTC years under President Biden, the response was the proposal of the One Agency Act (and a failed recent reconciliation attempt along the same lines) to fold the FTC’s competition functions into the DOJ Antitrust Division.

The point is, where the executive gains relative control over the FTC, Congress loses some of that control on the margin. That tension is minimized during periods of political alignment between the White House and Congress – such as now. But what about when the President is a Republican and Senate, House, or both are Democratic? What then? Does the Democratic Congress limit the Republican FTC’s budget? Does the minority party Congress strengthen oversight of the (Presidential) majority FTC? Cut its budget? Demand the nomination of minority party Commissioners? Or does the party controlling Congress see any value at all in the FTC run by the other party’s executive authority?

Agreement over the bipartisan business agenda of the FTC – when I was a Commissioner more than 90% of the votes were unanimous across party lines – was a constraint on this type of Congressional control. But I would not expect the same in a world with an executive FTC with members drawn from one party while another controls Congress. The FTC has been becoming more partisan over at least the past 20 years. The days of political agreement over its bipartisan mission creating sufficient goodwill to survive major disputes have, in my view, long been dead.

4. The Loss of Dissenting Viewpoints and Statements at the Commission is Hard to Replace – But Possible with Some Institutional Changes

I served as a minority Commissioner, i.e. a Republican Commissioner during a Democratic (Obama) Presidency. I am a big believer in the potential value created by strong minority opinions within the agency. The value is that the FTC can become an echo chamber on certain issues. Strongly held views inside the agency can become calcified. One only need to read the Supreme Court’s sharp rebuke of the FTC in AMG Capital or Axon for examples of situations in which long held FTC views, once exposed to rigorous testing and analysis outside the building, are found lacking rigor or sufficient intellectual or evidentiary foundation.

I set a record – which still stands, FWIW, which is little – for the highest rate of written dissents at the Commission during the modern era. I did not dissent simply because I enjoyed writing them. Though that is true. And I did not dissent because I thought it would ultimately change the view of the court. Back in my day, as far back as 2015, the FTC norm held that Commissioners generally did not write on matters that went to federal court. And the consensus bipartisan view was that the FTC did not have competition rulemaking authority and thus there was no such thing as a rulemaking dissent that would ultimately be picked up by the reviewing court. Things have changed! But the point of the dissents then and now remains: thoughtful written dissents are most valuable because they air important issues to the public and to the courts. And in equilibrium, a majority knowing its work will face close inspection internally, and potential exposure in a written dissent, will be much more careful with the facts and law. I did not view my role as a minority Commissioner with an eye toward the goal of breaking the agency or stopping its work. Sometimes I disagreed on the merits. And I viewed my “no” vote coupled with a written statement as to the specifics of my disagreement and the potential alternative path as one that would not only air the dispute for future FTCs to consider, but also would make this FTC better.

Whether that strategy worked is not for me to decide. But the point here is that, whatever strengths of the “executive FTC,” and to be clear – I am of the view that competition enforcement would be stronger and more efficient by eliminating the FTCs role altogether – loss of the internal dissent via an expert Commissioner is a real cost. I do not think there is any way around that fact. So it is best to face it.

I do think there are some institutional arrangements that a forward-thinking executive FTC could take on to replicate the role of minority Commissioners in order to improve the work product. Substitutes are available for this role, even if imperfect, of “red teaming” the majority’s work and ensuring that the echo-chamber culture that has run the agency into trouble in the past does not hinder its work. Now is not the time to go into these ideas in detail. But the FTC has available to it the ability to hire outside experts and consultants for these roles, or to assign them to strong thinkers inside the agency who do not agree with the majority’s current politics or enforcement priorities.

Again, the loss of minority voices is not to be celebrated. It is a cost to agency performance and to its credibility when it goes to court as an “expert” and asks courts to treat it as such. These alternative institutional arrangements give it a chance to mitigate some of that damage even if they do not eliminate it entirely.

Let’s shift from “big implications” to more practical ones.

5. Does Your Advocacy Strategy Change at the Executive FTC?

If the laws and facts do not change, then why should it? That’s a fair question. And I think this is the correct way to view things in large part. Commissioners from either party believe in law and facts even if they see them differently from time to time. And the FTC staff is certainly much more interested in law and facts than they are in who the individual Commissioners are at any given time. That is a totally sensible view of FTC advocacy on individual cases. But it is also a little bit naive.

FTC respondents have always tailored advocacy strategies to the Commissions they face. Sometimes in intelligent ways that frame the law and facts in the way that resonates the most with the Commissioner. Sometimes in silly ways. I cannot tell you how many times as a Republican Commissioner with a reputation for caring about economics some Big Law antitrust practitioner would come into my office on a matter and spew out talking points that were platitudes about free markets, or a random Hayek quote, or a derogatory shot at the majority rather than engaging on the analytical foundation of the case. These meetings did not end well whether the company’s counsel knew it or not at the time.

This will change some in meetings with Commissioners. Here’s a simple example. Even when facing a majority Commission vote that is likely to challenge, for example, your proposed merger, it might make sense to strongly pursue the vote of the minority Commissioners because a 3-2 vote signals to the federal court that the case is weaker than one voted out unanimously. Similarly, a written dissent from a Commissioner would provide not only a strong signal but also a roadmap to a favorable decision for the court from an expert. I’ve seen many matters succeed using precisely this strategy. Perhaps on the margin the majority is really only willing to go through with a 5-0 vote but does not have the stomach for a 3-2. In any event, clearly, this strategy is no longer on the table. For that matter, split votes among the Commissioners are probably gone as well with rare exceptions.

One implication of that development involves the strategic decision of how much and what kind of advocacy to do in cases where the staff and the Commission seem to have their mind made up before the parties meet with Commissioners for advocacy. This is a relatively common scenario. And with no possible dissenting Commissioners to attract, the rate of return on sharing all of your defense with the agency during advocacy is sharply lower in some cases.

To use a hypothetical example from the Khan FTC, imagine a transaction where the parties believe they should prevail on a Section 7 Clayton Act merger claim because large efficiencies mean the transaction does not substantially lessen competition. The Khan majority had expressly articulated its view that there is not an efficiencies defense to Section 7. When Commissioners Ferguson and Holyoak were in the minority, it might well still make sense to push these claims fully with staff and the Commissioners, to share evidence, and to share expert advocacy and analysis. That might be the case even if the vote would inevitably be a 3-2 vote to challenge the merger. But without minority Commissioners, what gain is there to the parties of persuading either staff or the Chairman? A practical reality of the new, executive FTC model is that there is more strategic thinking that must happen concerning what information to share, what to keep close, and who exactly we are trying to persuade.

6. Courts Just Got More Important

A corollary of the last point is that the role of the courts in holding agencies accountable just got larger and more important. Minority Commissioners played the role of sharpening claims or even deterring the majority from bringing bad claims over vigorous and persuasive dissents that courts might take up. That constraint against “bad” cases has been relaxed. Even with it, the FTC found its way in recent years to some stinging rebukes by the Supreme Court. But its general track record in day-to-day enforcement of the antitrust and consumer protection laws is good.

Internal constraints against “bad” cases are gone. I don’t mean to sound hyperbolic. That is how most agencies work. The Antitrust Division at the DOJ does not need to worry about written dissents and its record is every bit as good as the FTC’s over the past several decades. The desire to win in federal court is a strong one and the cost of losing is high. Courts were already a significant constraint upon the FTC. But the role will be more important than ever as the agency’s willingness to bring borderline or controversial cases increases and cases that would have received a 3-2 vote with written dissents but now are unanimously voted out.

7. The FTC’s Reputational Capital Derives at Least in Part From its Reputation as a Bipartisan Expert Agency, and It Is Going To Lose Some

Just when you thought that judicial deference to agencies was at its low point after the Supreme Court abandoned Chevron – and it is – the executive FTC is going to be operating with less reputational capital than previously. The FTC’s reputational capital, which is very useful to it in court, derives at least in part from its status as a bipartisan, expert agency.

To be clear, I’ve long argued that reputation has lost some of its luster and properly so. From a perfect record of ruling for itself in administrative adjudication that strains credulity (and due process) to watered down standards in 6(b) research studies and procedural shenanigans designed to deter otherwise lawful mergers and business practices, the FTC’s reputation as “expert” has long been in decline. And that is NOT because it doesn’t have plenty of expertise inside the building. In recent years the FTC has taken a step backwards from economics-driven Merger Guidelines and even from the consumer welfare standard as the guiding light to interpreting Section 5 of the FTC Act. Agency leaders in both the Biden and Trump Administrations have not been shy in arguing that economic analysis has gotten in the way of their enforcement objectives. Courts notice these things. And just at a time when the FTC is taking its most political turn, both in the last administration and this one, courts are abandoning deference to agencies.

I think this presents an interesting rub for the agencies. The Khan FTC (with minority Commissioners and all) handled the tension between their ideological preference against economic evidence and their desire to win cases by giving the former lip service while showing up to court with economic experts, sophisticated economic evidence, and largely conventional antitrust theories. It is too early to tell how the Trump FTC will handle the same. On the one hand, its stated objection to economic evidence and the role of economics in antitrust is less vehement than the Khan FTC (it mostly comes from a single Commissioner). On the other, the Trump FTC appears to have less interest in changing the law or running a revolution and more interest in winning cases. Wins require economic evidence and economics. And they require courts to take the agency seriously. It is a tension that an executive FTC will have to pay closer attention to than most.

8. Guidelines Ping Pong

I’ll admit I was a bit puzzled when the Trump FTC and DOJ chose not to revert to the Trump Merger Guidelines (or at least the Trump Vertical Merger Guidelines). It seemed like not only a move in the right direction in terms of substance and consistency with modern antitrust law and practice, but also a return to guidance documents adopted by the agencies under President Trump. Win-win? No?

Chairman Ferguson’s explanation for the decision suggesting that it does not make sense to constantly switch back and forth between merger guidelines because the business community wants certainty has some intuitive appeal. It is true enough that uncertainty in the form of merger guidelines that jump all over the place every four years are a cost to the business community. But I was never really persuaded by this argument. This is no surprise! I place significant weight on the guidelines function of teaching and communicating sophisticated economic concepts to generalist federal judges. And with that function largely abandoned by the Biden-Khan Merger Guidelines, my view is that the agencies are missing a grand opportunity to help influence the courts in the right direction. The judges can already read the statutes. What they need help with is understanding how to interpret economic facts. And the agencies should help them with a set of guidelines that do that. We currently do not have that.

That is the case for new Merger Guidelines or at least reverting to the Trump Guidelines. But in a world with an executive FTC with no minority Commissioners – I think Chairman Ferguson’s position makes more sense than I credited it for originally. Perhaps (very likely) he knew something I did not at the time he made it! In a world where an executive FTC is going to switch between parties with the White House every four or eight years or so, it does not make a lot of sense to spend 1-2 of those years revising Guidelines from a resource perspective.

To be sure, I’d rather drop the Khan FTC Merger Guidelines for a different document. But as I’ve argued elsewhere, I think the most likely outcome of keeping the Khan-Biden Merger Guidelines is that courts rely upon them less. There are plenty of decisions applying economic concepts and parties that will point judges in the direction of useful economic tools. I think the Merger Guidelines were a very valuable tool for the agencies precisely because they provided a rigorous analytical framework for courts. That benefit will disappear. But I view this much more as the abandonment of Merger Guidelines primacy as I do a choice in favor of the Khan-Biden Merger Guidelines. But that is a development worth watching.

9. Who Wants to Be a Commissioner?

An interesting question in a world where FTC Commissioners can be fired with no notice – even majority Commissioners – is who wants to be one? Plenty of people. No doubt. But the job does become more politically interesting and less intellectually interesting. And that shift I think says something about what you can expect for future appointments. Non-Chairman majority Commissioner (to put it plainly) becomes a far less interesting job. Votes will be overwhelmingly unanimous. The Chairman sets the agenda in line with the President’s agenda (so far so good) and the Commissioners follow along. Commissioners who might disagree are unlikely to do so where there is the threat of removal.

Historically, Chairmen have given broad swaths of policy areas of projects to majority Commissioners to keep them invested in the agenda. There is less of a need for that with the threat of removal. I’m sure that practice will continue if not only out of the goodwill of the Chairman. As a corollary, the business community is far less interested in the policy views of non-Chairman Commissioners other than for the fact that they might become Chairman one day or what their views might say about the President’s agenda.

It is an interesting shift. But I’m not sure if that job would be attractive to candidates more interested in the analytical and intellectual parts of the job rather than the political aspects. Of course, it is never all or nothing. And I don’t have a strong view about whether that is a good or bad thing. But my prediction is that the trend towards Commissioner appointments from the Hill (i.e. former Congressional staffers) and the states continues. That is not to say those folks are not also interested in the intellectual aspects of the job! Of course they are. But they are both familiar with and enjoy the political aspects as well. Whereas, I’m not sure many expert practitioners or academics want to leave their law firms or law schools for a job where they might be fired and are a bit less “in the action” on the margin.

Let’s conclude with a “big question.”

10. Can the FTC Stand When Humphrey’s Executor Falls?

I do not think it can in the long run. I’ve made the case elsewhere for folding the FTC’s competition functions into the DOJ Antitrust Division. I stand by that analysis and commend it to all of you (in a paper written along with Judge Ginsburg).

Let’s think about the key distinctive features of the FTC’s competition mission in particular:

Section 5 Unfair Methods of Competition

Administrative Adjudication

6(b) authority to conduct research and policy studies

The FTC has done a fine job on its own abusing each of these with sufficient regularity and consequence to create demand for elimination of the agency through the One Agency Act or otherwise. That they were able to avoid that at current is a bit besides the point. How does the fall of Humphrey’s Executor change things?

The idea that the FTC as an adjudicator can provide respondents due process or procedural fairness has already been dubious for some time. The delusion of the new, executive FTC as a neutral adjudicator is even harder to maintain Now with the executive FTC that delusion is even harder to maintain. The FTC already faces serious constitutional challenges to the Commission’s administrative adjudication process as well as Seventh Amendment challenges. The FTC Act contemplates a panel of bipartisan experts who would, neutrally, adjudicate the FTC’s vague “unfair methods of competition” standard. How can it possibly maintain that charade as a partisan body whose judges can be removed by the executive for decisions? I am very comfortable with the FTC losing its ability to engage in administrative adjudication. I do not think much good has come of it, while it has created ample opportunity for procedural opportunism and conduct inconsistent with the rule of law. But I do understand that viewpoint is a controversial one within even conservative antitrust circles where former Commissioners and academics have held out hope that the better angels of the FTC’s nature would emerge and put an end to procedural shenanigans. The record is already clear that the better angels did not prevail. But even the most optimistic about the role of administrative adjudication at the FTC would have a hard time making the case that the FTC can serve as a neutral adjudicator while also a partisan and direct extension of the executive branch.

It is difficult to imagine the FTC’s administrative adjudication function survives constitutionality challenges when the President can fire Commissioners acting in their role as judges. And that raises the question – as we take away signature distinctive FTC functions that differentiate it from the DOJ Antitrust Division – why do we need the FTC at all?

The conservative answer to this question ultimately is: “we do not.” The “unitary executive” based answer to this question is as clear as the efficiency-based answer. It has long been more efficient to have a single federal antitrust enforcer rather than two – as Judge Ginsburg and I have explained. The competition policy functions of our government are already widely distributed among 50 states and hundreds of federal sectoral regulators with some claim to competition authority. Conflict among the FTC and DOJ on substantive and procedural issues and inconsistencies created by the FTC’s unique authority have been the rule rather than the exception. And the FTC’s distinctive features have imposed costs on the enforcement mission that are much greater than their benefits. The fall of Humphrey’s Executor will inevitably mean the death of the FTC’s role as administrative adjudicator. That is a good thing in its own right because the FTC has abused that role historically. But in the long run, the case for an FTC whose competition functions largely replicate the DOJ gets weaker and weaker.

The One Agency Act was defeated this time in reconciliation largely because of the Trump Administration’s enthusiasm for the Ferguson FTC’s initiatives. That says much for Chairman Ferguson – because the case for the FTC is an uphill climb against logic that conservatives have invoked to consolidate or end other agencies (e.g. CFPB). But in the long run I predict that the FTC will not continue its competition function without its role as neutral administrative adjudicator – a role that is now impossible to fulfill.

That’s all for today. Next we will turn to recent developments in the Robinson-Patman Act space. The Commission dropped the Pepsi case – as we predicted it would here. But where does that leave the RPA’s revival?

In the meantime, please subscribe, upgrade to paid, and send to your friends. And do not hesitate to contact me with questions, requests for columns, and ideas!

Josh, I agree with your post across the board. However, I am seriously concerned about the limitations, if any, on the reveral of Humphrey's Exec. I oppose any effort to give the Executive and, God forbid, the Legislative control over the Central Bank These people cannot balance their own budget. Also the Court's decision would have to protect administrative courts. District Judges will resign in droves if they are stuck adjudicating Social Security and a host of other agencies' cases